![BollandHoward]()

Howard the Duck. Art by Brian Bolland.

This article is a history of the editorial and business relationship between Marvel Comics, their representatives, and the late writer Steve Gerber (1947-2008). Its focus is their dealings over Howard the Duck, Gerber’s signature character.

The piece has its origins in a historical series I’ve been intermittently working on called Jim Shooter: A Second Opinion. The series is a reexamination of the frequently maligned tenure of the Marvel Comics’ editor-in-chief between 1978 and 1987. The third article, still in progress, is planned to cover Shooter’s alleged conflicts with writers, artists, and editorial staffers in the months that followed his taking the editor-in-chief position. Gerber, the co-creator, writer, and editor of Marvel’s Howard the Duck series, was fired shortly after Shooter took over. An account of his termination seemed in order. Most writers have treated the termination as going hand-in-hand with the 1980 lawsuit Gerber filed over ownership of Howard, so I looked into that as well.

In 2009, Gerber’s close friend Mark Evanier wrote, “The whole matter of Steve’s legal problems with Marvel [...] is a very complicated situation which has never been accurately described in any past reporting.” He’s right. I discovered that the lawsuit in particular had never received anything close to adequate coverage. Lawsuits are a matter of public record, but not one writer appeared to have even read the complaint filing. Upon realizing that no one had done the most basic legwork on this episode, I shifted gears. I set aside the Shooter article, and began researching Gerber in depth instead. Presenting the record with him, rather than arguing it with Shooter, seemed a more urgent undertaking.

The lawsuit’s being public record gave me the opportunity to construct extended parts of the narrative from primary source documents and other court filings. Whenever possible, I have derived my account from contracts, business correspondence, and sworn court declarations. It’s preferable to having to rely on media interviews and earlier writers’ treatments of the matters at hand. With primary source documents, I don’t have to worry to what extent a person’s prejudices and agendas may be skewing their portrayal of a letter or contract; I can just see the document for myself. And while probably no first-person account is entirely free of inaccuracies, people tend to be more rigorous in statements made under oath than when talking to a journalist. In telling the story of the lawsuit, I’ve tried to do so as accurately as possible. In effect, I’ve sought to meet the challenge Mark Evanier’s statement makes. This article is intended as a definitive account.

I note that I am not looking for the imprimatur of, among others, Mark Evanier. He has spent many years working to develop a reputation as a comics historian, and several in the comics community put a good deal of weight on his opinion. I expect that, as Gerber’s friend, he will find the article distasteful. The depiction of Gerber’s various dealings with Marvel is an unvarnished one. I have no interest in providing a necessarily complimentary view of anyone involved. For my part, all I can I say is I’ve done my best to be both skeptical and fair towards Gerber and the others. I believe my presentation is both accurate and thorough. I hope those who would prefer a partisan portrayal favoring Gerber can respect the article as a conscientious effort. For those who think they can do better, I’ve made it as easy as I can for them to improve upon my work.

In addition to the bibliography, there is an accompanying post titled “The Howard the Duck Documents.” (Click here.) It is a trove of primary source materials related to the case. One will find copies of all of Gerber’s 1970s Marvel contracts, every extant piece of correspondence relating to his 1978 termination, and the most significant documents filed with the court. These include the lawsuit complaint, the extended declarations and responses by both sides in the complaint’s wake, and the judge’s final order to dismiss the case. For those curious as to what isn’t included, there is also a copy of the complete case docket, which lists every filing in the suit. Most of this material has never been published or even reported on before. It is all in the public domain, so those interested are free to copy and publish it for their own use.

The complete case records, reportedly two cartons of documents, are in the National Archives at Riverside, California. The staff there was immensely helpful in providing the documents I sought. I believe anyone looking to fill perceived holes in my research will find them just as invaluable. They definitely have my thanks.

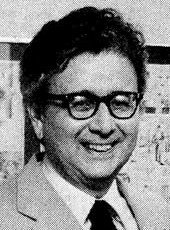

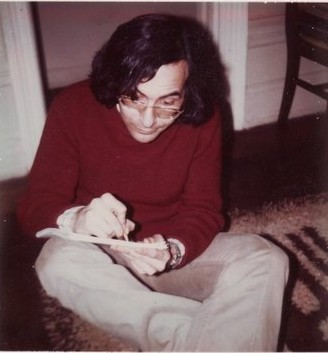

![Steve Gerber]()

Steve Gerber

Steve Gerber was born in St. Louis, Missouri on September 20, 1947. He graduated from Saint Louis University in 1969 with a B. A. in communication. In 1972, while working as a copywriter for a St. Louis advertising agency, he contacted Marvel editor Roy Thomas about working for the publisher. Gerber and Thomas had met through Missouri comics-fan circles during the 1960s. Thomas, as he had previously done for fellow Missourians Denny O’Neil and Gary Friedrich, arranged for Gerber to join the company’s staff as an editorial assistant. The primary responsibility was proofreading. His salary would be $125 a week. (Adjusted for inflation, this would be the equivalent of just over $700 today.) Gerber, who was then 24, relocated to New York City, where Marvel was based.

![Adventure into Fear #11 (December 1972), Steve Gerber's solo scripting debut.]()

Adventure into Fear #11 (December 1972), Steve Gerber’s solo scripting debut.

Like other editorial employees at Marvel, Gerber supplemented his income with freelance scriptwriting for the company’s publications. According to the Grand Comics Database, his first published credits appear in the December 1972 issues of

The Incredible Hulk (an episode co-written with Roy Thomas),

Shanna the She-Devil (co-written by Carole Seuling), and

Adventure into Fear, featuring Man-Thing. Given Marvel’s cover-dating practices, the comics probably reached newsstands in September of 1972. Gerber most likely did the scripting for them that May. The Man-Thing feature was Gerber’s first series assignment, and he scripted it on a monthly basis for nearly three years. Shortly after embarking on the Man-Thing assignment, he also took over the scriptwriting duties on the

Daredevil and

Sub-Mariner series. At the end of 1972 or early 1973, he left his staff position to focus full-time on freelance writing for the company.

All of Gerber’s scriptwriting for Marvel at this time was done on a work-made-for-hire basis. Marvel owned all intellectual-property rights to the work he did. This was before 1978, when the 1976 Copyright Act’s mandate that work-made-for-hire relationships be agreed to in writing at the outset went into effect. Under the Copyright Act of 1909, as elaborated by federal-appeals-court decisions in Yardley v. Houghton-Mifflin (1939) and Brattleboro Publishing v. Winmill Publishing (1965), an independent-contractor relationship was assumed to be work-made-for-hire in the absence of a clear agreement to the contrary. Additionally, Marvel frequently stamped the back of freelancer checks with a legend that had, with the check endorsement, the freelancer acknowledge Marvel’s ownership of the intellectual-property rights to the work. One legend Marvel used reads:

By endorsement of this check, I, the payee, acknowledge full payment for my employment by Magazine Management Company, Inc. [Marvel's 1960s and early 1970s parent company] and for my assignment to it of any copyright, trademark, and any other rights in or related to the material, and including my assignment of any rights to renewal copyright.

This and similar legends have often been portrayed as transfer agreements, but according to the prevailing judicial precedents, the rights had already been transferred by dint of the freelancer relationship with the publisher. In practice, the legend was a redundancy that ensured the freelancer had been notified as to the publisher’s policy, and that the policy covered the work at hand.

There was nothing particularly unusual about Marvel’s conduct. Under the indivisibility doctrine that emerged from the 1909 copyright law, publishers could not, among other things, take action against infringement without ownership of the intellectual-property rights. Freelancer contributions were all but universally assumed to be work-made-for-hire throughout the periodical publishing industry, including newspapers, non-comics magazines, and other comics publishers. Back-of-the-check legends were not uncommon, either, and were used by such top-paying publishers as Mad and Playboy.

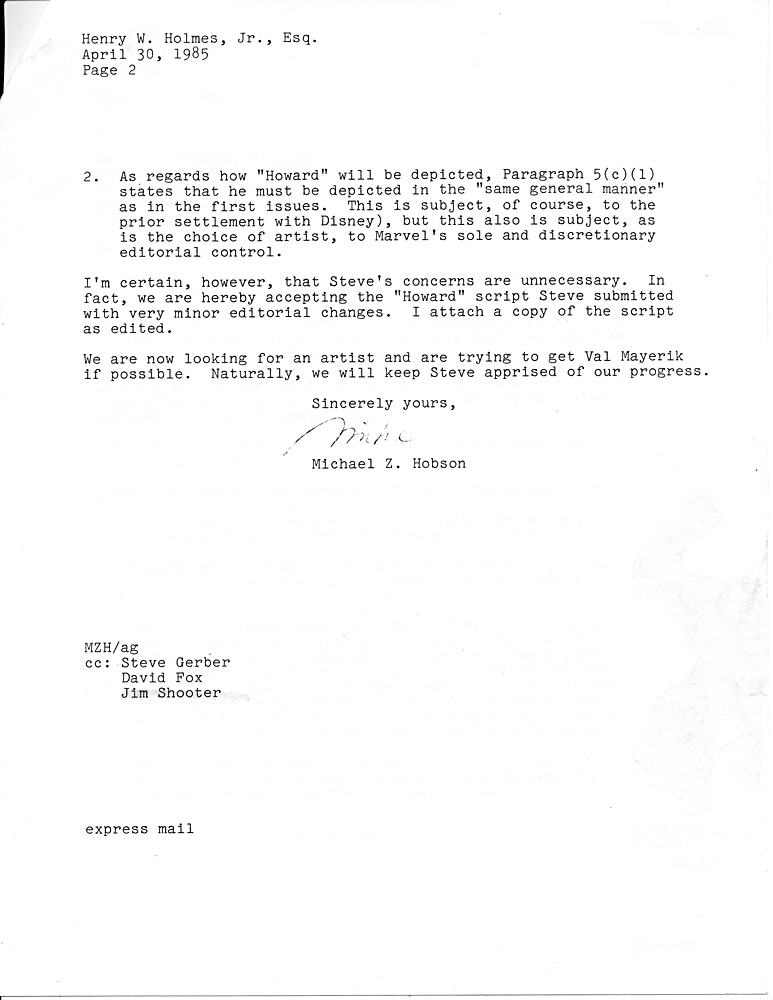

![htdaif19]() The first appearance of Howard the Duck. From Adventure into Fear #19, as reprinted in Essential Man-Thing, Vol. 1.

The first appearance of Howard the Duck. From Adventure into Fear #19, as reprinted in Essential Man-Thing, Vol. 1.

Gerber gradually created a large supporting cast for the Man-Thing feature, including the teenage sorceress Jennifer Kale, Dakimh the Enchanter, and Korrek the Barbarian. One year into the series, in Adventure into Fear #19, he and artist Val Mayerik introduced what would quickly become his most famous creation: a talking, cigar-smoking duck from another world named Howard. The issue, cover-dated December 1973, would have reached newsstands that September. It was most likely written the previous spring. In a 1976 interview, Gerber described when the initial idea for Howard the Duck came to him:

[Howard was created as] a joke. It was the only sight gag I could think of to top Korrek jumping out of a jar of peanut butter in Fear #19[.] I told Val to have a duck come waddling out of the bushes. (Kraft 10)

Gerber also described Val Mayerik’s contribution:

[T]he cigar was Val Mayerik’s creation. So was Howard’s clothing. I just told Val, “Don’t make him look too much like Donald, and for God’s sake, don’t dress him in a sailor suit. (Kraft 10)

Marvel ostensibly paid for Gerber’s work on the issue with a June 1, 1973 check for $285.00. The back of the check was stamped with the rights acknowledgement legend.

(For a copy of the check, both front and back, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

The Howard character didn’t last long in the feature. Gerber told Jon B. Cooke in 1999 that editor Roy Thomas ordered him to remove Howard from the series “as fast as you can” (Cooke 61). Midway through the subsequent episode, published in The Man-Thing #1 (January 1974), Gerber and Mayerik had Howard fall off a giant stepping-stone bridge into an inter-dimensional void, apparently never to be seen again. The other characters considered him dead.

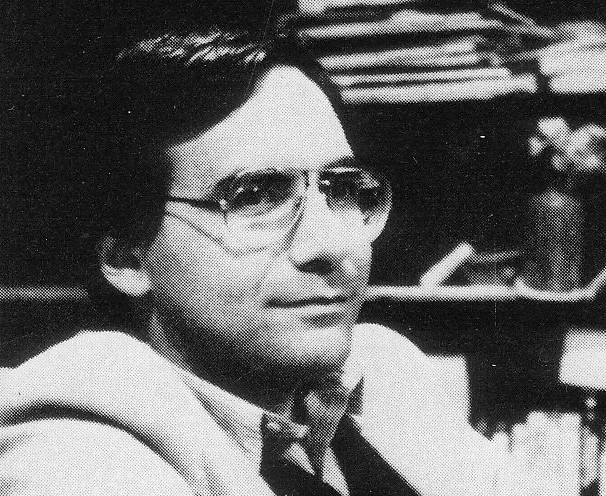

![htdmt10001]()

The assumed death of Howard the Duck. From The Man-Thing #1, as reprinted in Essential Man-Thing, Vol. 1.

But Howard had struck a chord with several readers. According to Gerber in 1975:

People were taken with him immediately. The office was flooded with letters; there was one wacko who sent a duck carcass from Canada […] saying, “Murderers, how dare you kill off this duck?” There was the incident at a San Diego Comics Convention where somebody asked Roy, I believe, who was speaking there, whether Howard would ever be coming back, and the auditorium stood up and applauded. Stan [Marvel publisher Stan Lee] was being asked about it everyplace he went on the college [lecture] circuit. (Kraft 10)

![htdgsmt4a]()

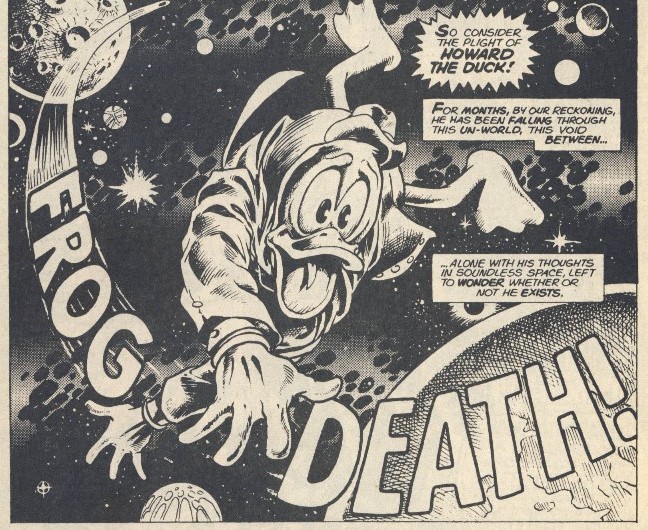

The return of Howard the Duck. From the opening page of the solo Howard story in Giant-Size Man-Thing #4 (May 1975), as reprinted in Essential Howard the Duck, Vol. 1

Marv Wolfman, then the editor of Marvel’s black-and-white magazine line, claims that he approached Gerber about featuring Howard in those titles (Dean 42). However, the decision was made to reintroduce the character in the color comics. Gerber and artist Frank Brunner put together a nine-page story that was published as a back-up feature in Giant-Size Man-Thing #4 (May 1975). The story picked up Howard right where The Man-Thing #1 episode had left him. The opening page showed him falling through the seemingly endless void. The top of the second page had him landing in a vacant lot in Cleveland. Over the course of the story, he befriends a pair of local boys, does battle with an anthropomorphic frog that’s terrorizing the neighborhood, and ends up arrested by the police. Gerber and Brunner did a follow-up story for the next issue of Giant-Size Man-Thing. The response to the stories was favorable, and the go-ahead was given to launch Howard in his own title.

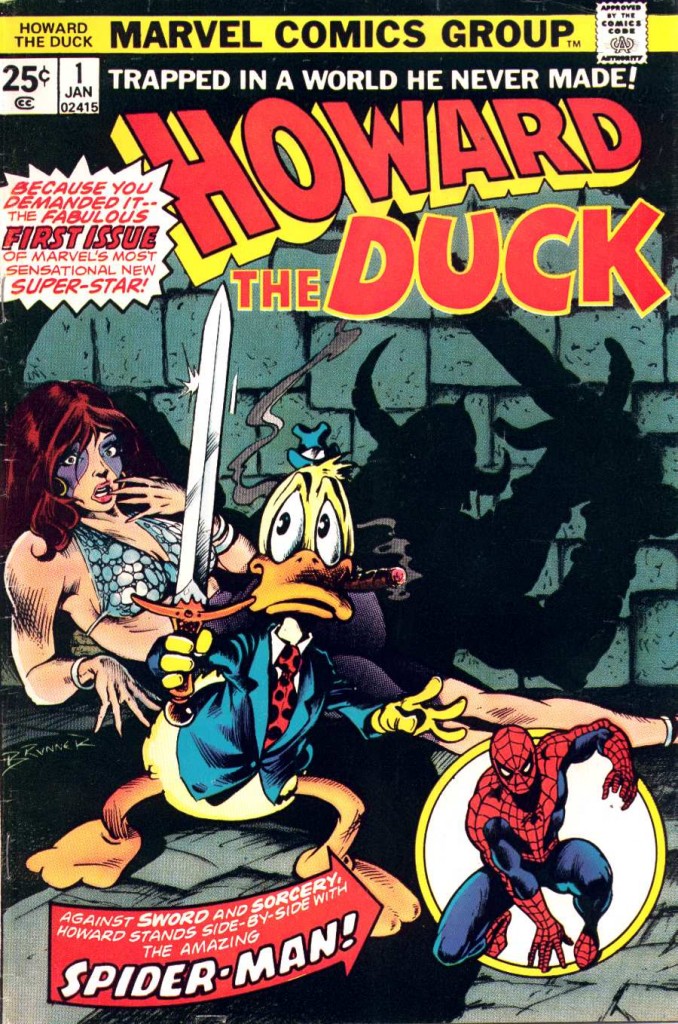

![Howard the Duck 01 - 00 - FC]()

Marvel’s circulation director Ed Shukin didn’t have much faith in the new series. For the first issue, he ordered a print run of 275,000–Marvel’s minimum at the time for a standard-size color newsprint comic. That first issue (cover at left) shipped to newsstands in October of 1975. It promptly sold out. Looking back on the first issue’s sales, Shukin told The New Yorker writer Mark Singer, “I underestimated that duck” (Singer 30). Unfortunately, many of the copies weren’t sold to readers. Comic-book collectible dealers reportedly snapped up every copy they could find through newsstand vendors and distributors. They intended to hoard the books and then sell them at vastly inflated prices. One dealer, Jim Kovacs of Cleveland, claimed to have bought 900 copies the day the issue went on sale. He told the Washington Post he followed the distributor’s truck while it made its deliveries. In 1977, the average price of the issue among back-issue dealers was $12.50, a mark-up of 5,000 percent over the cover price of 25¢. Gerber, reflecting on the situation in 1999, said:

I was angry as hell. I felt as if the book had been sabotaged by the very people who supposedly liked the character […] The sales on [Howard the Duck issue] #2 were respectable. I don’t recall exactly what the sales figures were, but I think it would’ve done a lot better–the series would have done a lot better–had that first issue reached the stands. (Cooke 64).

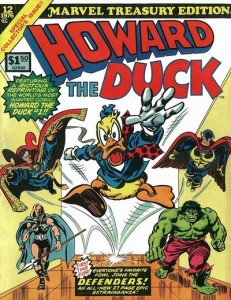

![25899]() In the summer of 1976, partly in response to the unmet demand for the first issue, Marvel issued a tabloid-size Treasury Edition (cover at right). Along with a new episode, it reprinted the first issue’s story and all the character’s prior appearances. The material from the initial Man-Thing stories were, apart from one scene, limited to excerpts featuring the sections in which Howard appeared. Gerber and Val Mayerik produced a new splash page introducing the excerpts, and Gerber provided a text dialogue between Howard and a “Voice from on High.” The dialogue filled the half-page above the panels featuring Howard’s initial appearance from Adventure into Fear #19.

In the summer of 1976, partly in response to the unmet demand for the first issue, Marvel issued a tabloid-size Treasury Edition (cover at right). Along with a new episode, it reprinted the first issue’s story and all the character’s prior appearances. The material from the initial Man-Thing stories were, apart from one scene, limited to excerpts featuring the sections in which Howard appeared. Gerber and Val Mayerik produced a new splash page introducing the excerpts, and Gerber provided a text dialogue between Howard and a “Voice from on High.” The dialogue filled the half-page above the panels featuring Howard’s initial appearance from Adventure into Fear #19.

Gerber may have felt Howard would have done better had it not been for the speculation frenzy, but sales appear to have been healthy. Ed Shukin told The New Yorker the print-run on a new issue in 1977 was 400,000 copies, a 45% increase over the pressing of Howard #1. Newsstand periodical print orders generally reflect an expected sell-through rate of 50%, so Howard‘s paid circulation was probably about 200,000 copies per issue. Marvel’s confidence in the series’ sales was also reflected by the decision to bump it from bi-monthly to monthly status with the seventh issue.

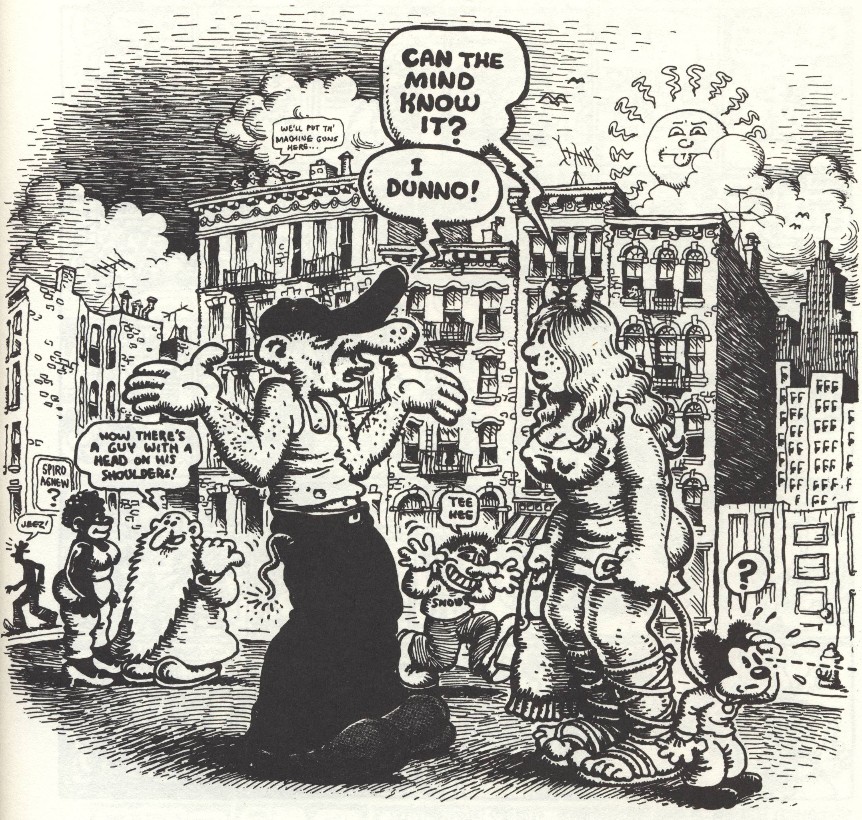

The feature had strong cult appeal. The character’s alien perspective, combined with the strip’s setting in Marvel Comics’ superficially quotidian fantasy world, provided Gerber with an effective vehicle for satirical social commentary. The setting allowed him to parody comics and other pop-culture material with abandon. The satirical tropes were often clever and layered. Gerber also managed to imbue the character with a forlorn air of existential absurdity. He occasionally hit notes that, for all the series’ juvenile goofiness and adventure-fantasy trappings, were far more characteristic of literary fiction than anything seen up to that point in American comic books. Steve Gerber is widely considered the most accomplished writer of 1970s English-language adventure comics, and Howard the Duck’s better moments are much of the reason why.

![Frank Brunner]()

Frank Brunner

However, all was not good behind the scenes. Artist Frank Brunner was growing increasingly unhappy. In a 1999 interview with Jon B. Cooke, Brunner said that he felt he should have been credited as the co-writer, not just co-plotter, of the story in

Howard the Duck #1. At the very least, a change in the credits would entitle him to larger payment with reprints. Creative tensions with Gerber arose as well. With the second issue, Gerber began writing the stories full-script, and Brunner found Gerber’s insistence on delivering the script piecemeal oppressive. He told Cooke, “I couldn’t pace the story! [...] full script is one thing, you can at least pace it, but when you get it in pieces, I don’t know where to put the big dramatic scenes!” Brunner was also at odds with Marvel’s policy at the time for returning original art, and it led to arguments with Gerber. The policy was for a story’s scriptwriter to get two of the pages for a standard 17-to-19-page story, with the remainder divided in a two-thirds/one-third split between the penciler and inker. (Jim Shooter, Marvel’s editor-in-chief between 1978 and 1987, permanently eliminated the writers’ share in 1980.) At the time, a few of the company’s scriptwriters didn’t see why they should be entitled to the original pages and returned them to the artists. Gerber, though, wasn’t among them. He refused to accommodate Brunner’s requests to turn over the pages he’d been allocated. Finally, after Brunner heard reports of the first issue’s sales, he asked Marvel to increase his page rate. He was refused. He quit after turning in the art for the second issue. The third issue was pencilled by John Buscema, and then Gene Colan took over as the series’ regular artist. Steve Leialoha, who inked the Brunner episodes, stayed on as the series’ inker.

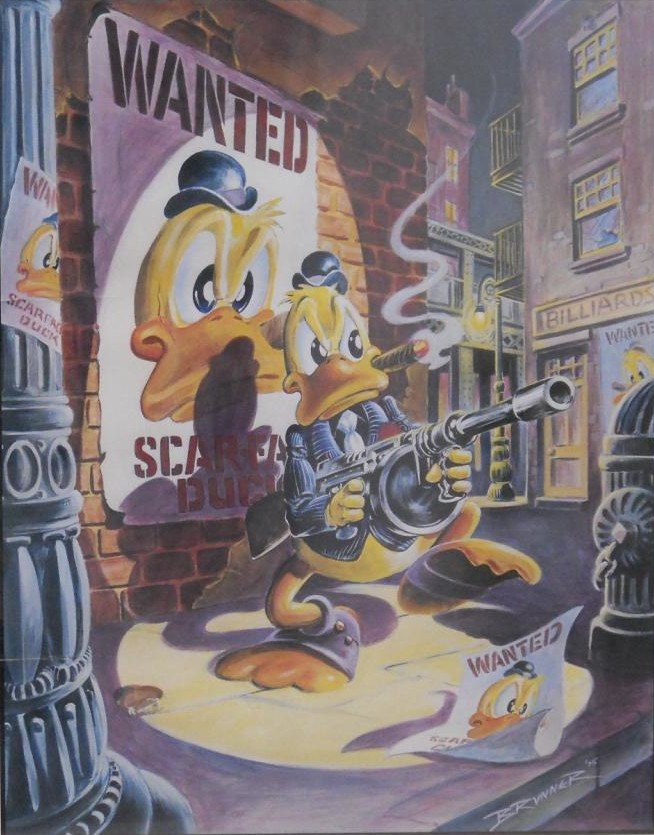

![ScarfaceDuck]()

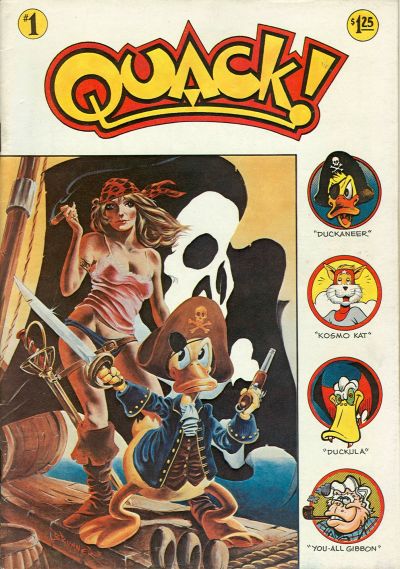

![49139]()

The Scarface Duck poster (left) and Quack #1, featuring the Duckaneer (right)–artist Frank Brunner’s 1976 attempts to capitalize on Howard the Duck’s success.

Brunner didn’t go off quietly into the sunset. He immediately set himself up in competition with Howard and started doing his own cartoon duck material. His attitude was, “I was filling a void left by slow-moving Marvel [...] which did not immediately see the potential of the fan market–or of the duck” (Howe 182). The first product was a poster print, sold and distributed via mail order, titled Scarface Duck. It depicted a Howard-style duck in 1930s gangster-movie trappings. The second was a new duck-comics feature titled “The Duckaneer,” done in collaboration with inker Steve Leialoha. It debuted in the premiere (July 1976) issue of Quack!, published by Star*Reach for exclusive distribution to the nascent comic-book specialty market. Marvel doesn’t appear to have given either project any mind, but Gerber was not happy. After learning of the poster, he contacted Brunner and demanded a share of the profits. Brunner refused, saying to him, “Which part of the print [...] did you write or draw? What part of the deal did you arrange?” (Howe 183). It’s not known how successful these projects were, but Brunner all but abandoned duck-related efforts after the first Duckaneer story was published. He did a few media-parody duck prints for the poster market in the years that followed, but almost all his subsequent output was devoted to non-duck material.

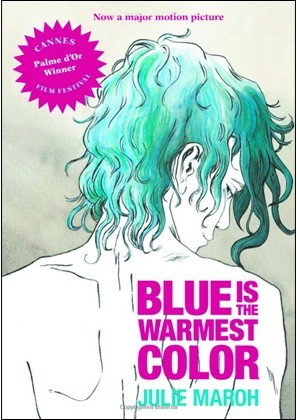

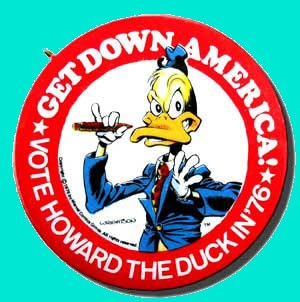

![WrightsonHoward]()

The “Vote Howard the Duck” pin-back button. Art by Bernie Wrightson.

Steve Gerber had merchandising ideas of his own. On March 12, 1976, he entered into a licensing agreement with Marvel for the manufacture and sale via mail order of “Vote Howard the Duck in ’76” pin-back buttons. Marvel would be paid a royalty of five percent for each one sold.

(For a copy of the March 12, 1976 button licensing contract, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

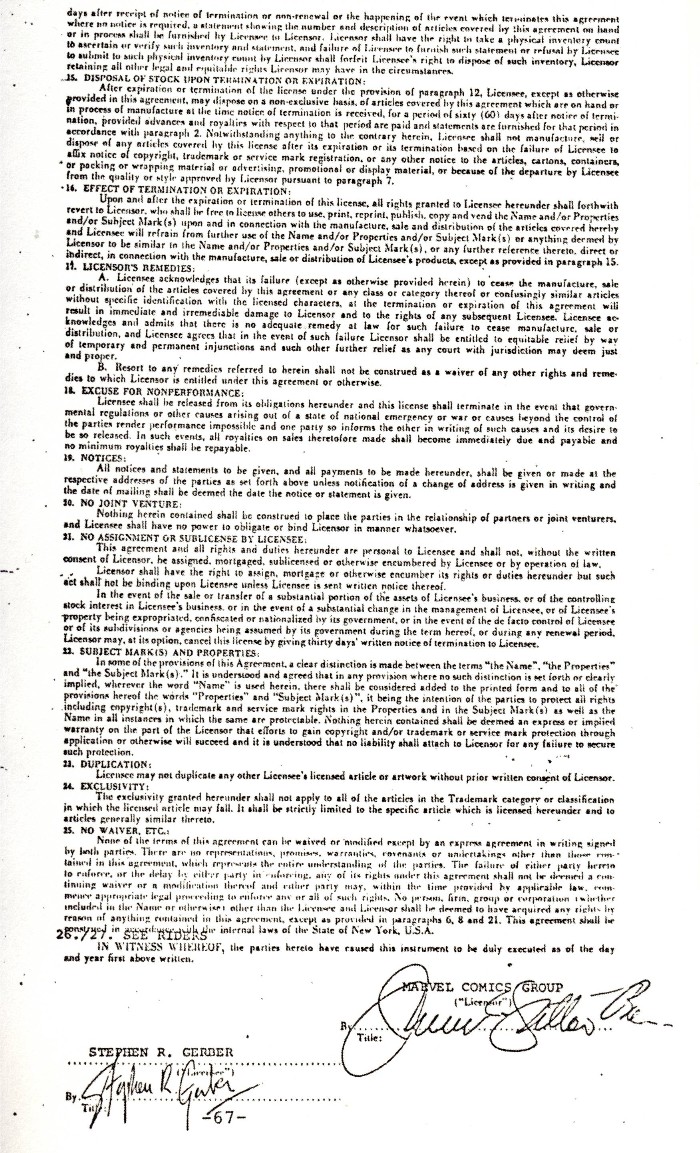

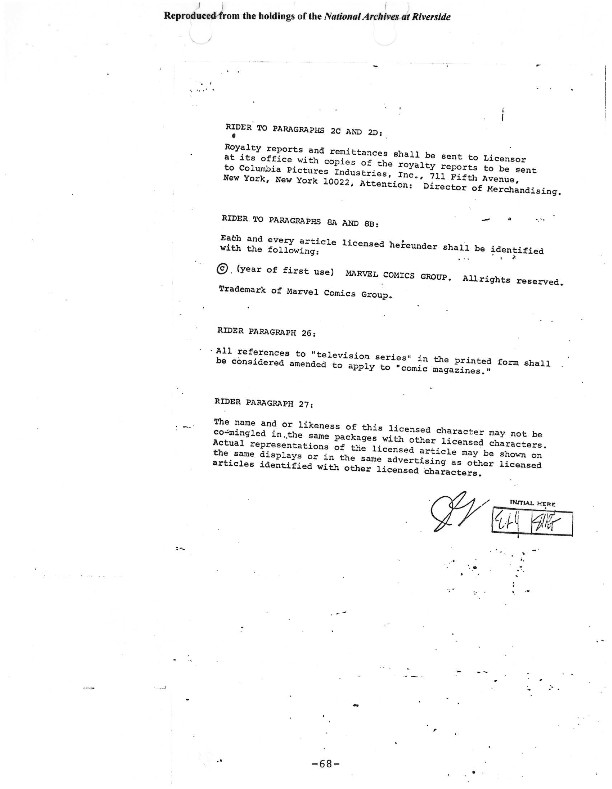

The licensing contract should have clarified any ambiguity that may have existed at that point with regard to ownership of the character. Section 4 of the agreement, titled “GOOD WILL, ETC.” includes this statement:

Licensee [Gerber] recognizes the great value of the Name and Properties and Subject Mark(s) and of the goodwill associated therewith and acknowledges that the Name and Properties and Subject Mark(s) and all rights therein (including copyright) and goodwill pertaining thereto belong exclusively to Licensor [Marvel].

The contract’s preamble specifically defines the terms used. The term “Name” refers to Howard the Duck’s “name, character, symbol, design, likeness, sounds and visual representation and/or each of the individual components thereof”. The term “Properties” means “copyright in literary and/or artistic materials featuring, containing and/or consisting of the names, characters, symbols, designs, likenesses, sound and visual representations” of Howard the Duck. The “Subject Mark(s)” are defined as “Trademark registration(s) of the Name and/or components thereof”. Gerber acknowledged in the contract that Howard was Marvel’s exclusive property.

Additionally, in Section 5 of the agreement, titled “LICENSOR’S TITLE AND PROTECTION OF LICENSOR’S RIGHTS,” the contract says, “Licensee agrees that it will not during the term of this agreement, or thereafter, attack the title or any of the rights of Licensor or Licensor’s grantors in and to the Name and/or Properties and/or Subject Mark(s) or attack the validity of this license.” In other words, Gerber contractually agreed to never sue over or otherwise challenge Marvel’s exclusive proprietary rights to Howard the Duck.

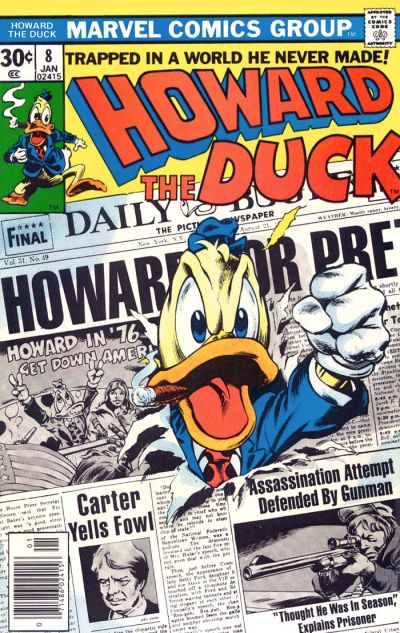

![Howard-the-Duck-81]() Gerber hired artist Bernie Wrightson, best known as the co-creator of DC Comics’ Swamp Thing character, to do the artwork for the button. It retailed for one dollar plus a quarter for shipping. Checks were to be made payable to Gerber, who handled the orders through Mad Genius Associates, a cooperative with fellow comics scripters Mary Skrenes, Jim Salicrup, Don McGregor, and David Anthony Kraft. The comic-book series was used to promote the button. It was advertised in the letters column of the fourth issue. A few months later, an episode revolving around the character’s presidential campaign was featured in issue #8 (cover at right). It reached newsstands in October of 1976. (The issue was cover-dated January 1977.) The faux presidential campaign contributed to the buzz around the series, and over the next year or so Gerber was interviewed for articles about the feature in Circus, Playboy, and the Washington Post.

Gerber hired artist Bernie Wrightson, best known as the co-creator of DC Comics’ Swamp Thing character, to do the artwork for the button. It retailed for one dollar plus a quarter for shipping. Checks were to be made payable to Gerber, who handled the orders through Mad Genius Associates, a cooperative with fellow comics scripters Mary Skrenes, Jim Salicrup, Don McGregor, and David Anthony Kraft. The comic-book series was used to promote the button. It was advertised in the letters column of the fourth issue. A few months later, an episode revolving around the character’s presidential campaign was featured in issue #8 (cover at right). It reached newsstands in October of 1976. (The issue was cover-dated January 1977.) The faux presidential campaign contributed to the buzz around the series, and over the next year or so Gerber was interviewed for articles about the feature in Circus, Playboy, and the Washington Post.

With the ninth issue, Gerber took over as the series editor. Judging from Sean Howe’s account in Marvel: The Untold Story, the expanded authority on the title was intended to mollify Gerber after he’d had his scriptwriting assignment for Marvel’s The Defenders series taken away (Howe 189). Gerry Conway, who had recently vacated Marvel’s editor-in-chief position, had negotiated a large contract with the publisher. It called for him to write and edit eight separate comic-book series. Five of the titles he took over had already been vacated by their regular writers, and two new ones were created to accommodate his quota. Someone, though, was going to have to be stripped of a series assignment for Conway’s benefit, and Gerber was made the sacrificial lamb. The freelance editing fee was a small fraction of what he had made writing The Defenders, but it seems the additional autonomy with Howard made up for the financial hit. And an opportunity for Gerber to make more money from Howard was just around the corner.

![gerberhgc2]()

The October 16, 1977 Sunday episode of the Howard the Duck newspaper strip.

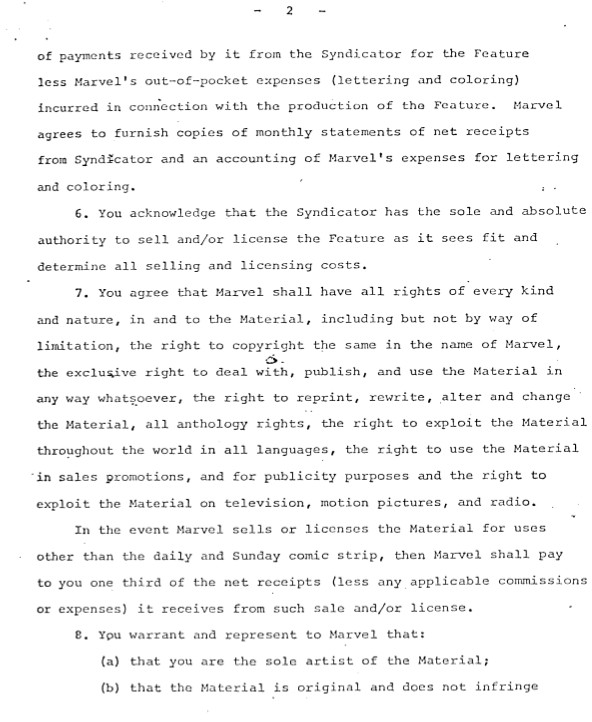

In early 1977, Marvel and the Tribune & Media Syndicate decided to launch Howard the Duck as a daily newspaper strip. Gerber signed a contract with Marvel to write it on March 17. He would be paid one-third of Marvel’s share of the syndication monies after lettering and coloring expenses were deducted. Gerber was further entitled to one-third of any money Marvel received from licensing Gerber’s newspaper-strip material to other media. According to syndicate president Denny Allen, nearly a hundred newspapers initially subscribed to the feature (Smith 37). It debuted on June 6, 1977. Gene Colan was the strip’s first artist.

(For a copy of Gerber’s March 17, 1977 newspaper-strip contract, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

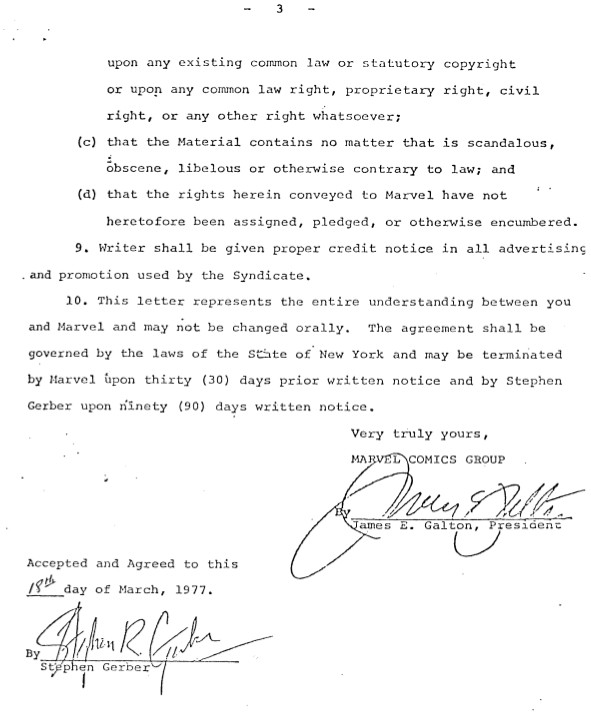

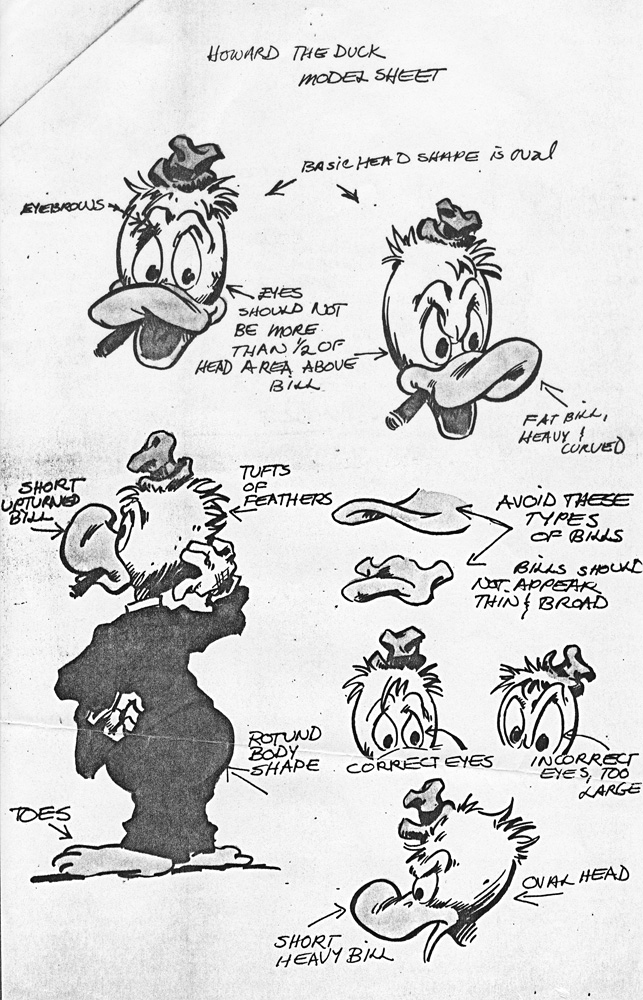

In the first half of 1977, The Walt Disney Company contacted Marvel out of concern that Howard infringed on their trademarks for Donald Duck and related duck characters. In Marvel’s official account of what happened, published in 1980, Steven Grant wrote:

Disney’s licensees overseas suddenly saw their markets threatened when competitors issued the adventures of Howard The Duck. (In countries where comics are translated into languages other than English, the word “duck” is synonymous with “Donald Duck,” and has been for more than 40 years. Simply by virtue of the word “duck” in his name, Howard became what no comics character had been before: a threat to Donald Duck.) The overseas licensees took their grievances to Disney, who in turn contacted Marvel. (26)

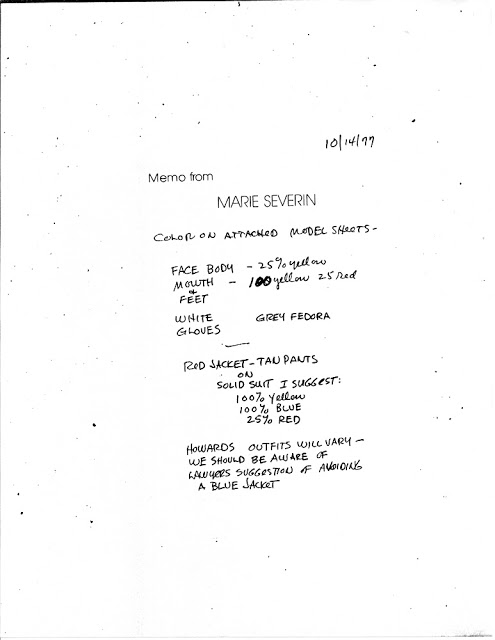

The two companies quickly worked out an agreement, and Disney artists redesigned Howard’s appearance. The character would now have an oval head, proportionately smaller eyes, and a short, fat, upturned bill. He would also have toes, brows, and a rotund body. Most conspicuously, the previously trousers-less Howard would now be wearing pants. On June 30, 1977, Marvel art director John Romita issued a memo detailing the changes, including color codes.

(For the redesign model sheets, the first page of the Romita memo, and a subsequent related memo by Marvel production artist Marie Severin, see The Howard the Duck Documents.)

In his public statements of the time, Gerber seemed fairly nonchalant about the redesign. He told the Washington Post that he consequently might “just give Howard a whole new wardrobe, turn him loose in Saks and see what he comes out with” (Turan B2). However, there’s little doubt that privately, Gerber greatly resented what had happened. (His intense dislike of the redesign became publicly known with the release of a 2002 Howard comics project.) Gerber’s anger appears to have quickly found its way into the comic-book series.

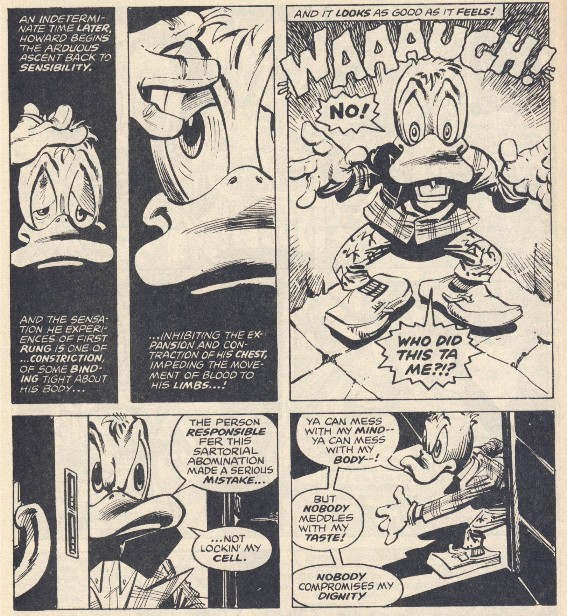

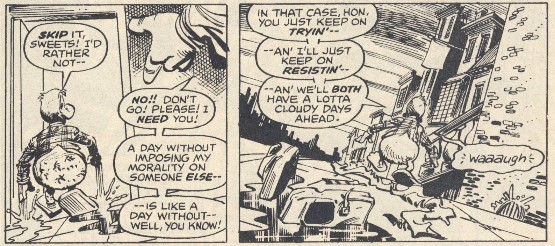

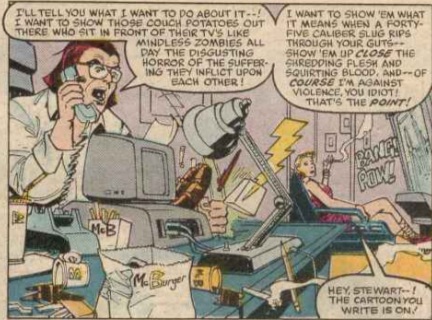

![htd210001]()

From Howard the Duck #21, as reprinted in Essential Howard the Duck, Vol. 1.

Howard‘s 21st issue, pencilled by guest artist Carmine Infantino, reached newsstands in November 1977. (The indicia date was February 1978.) The episode was most likely written in July, shortly after the redesign specs were issued. On the surface, it was a lampoon of anti-pornography and other media-decency activists, with a few jabs taken at anti-gay-rights advocate Anita Bryant. But with knowledge of the behind-the-scenes goings-on, parts of the story take on an additional meaning: Gerber was also expressing his contempt for Marvel’s settlement with Disney. The activists, who call themselves the SOOFI, are urban terrorists. Their leader targets Howard for conversion due to his “youth appeal” and “kind of Saturday morning wholesomeness.” Howard is kidnapped, and when he awakens in the SOOFI’s base of operations, he discovers he has been outfitted in entirely new clothes, including pants. He finds the pants physically uncomfortable and an affront to his dignity. While explaining the wardrobe change, the SOOFI leader remarks on Howard’s formerly bare-bottomed appearance with disgust. The SOOFI leader then attempts to brainwash Howard by subjecting him to a device called the Blanditron, but it has no effect. Howard then punches the SOOFI leader and leaves. The final panel has Howard walking away from the reader. The discarded pants are left lying on the pavement. He says to the SOOFI leader, “[...] you just keep on tryin’–and I’ll just keep on resistin’–an’ we’ll both have a lot of cloudy days ahead.” (Emphases in the original.) Gerber seemed to be saying that although Marvel was willing to give in to Disney (considered by many a “Blanditron” of popular culture), he wasn’t about to capitulate. Howard would not appear in pants for the rest of Gerber’s tenure as writer-editor.

![htd21a]()

The ending of Howard the Duck #21, as reprinted in Essential Howard the Duck, Vol. 1

Marvel’s editorial and legal operations were in almost complete disarray, which is most likely how Gerber was able to get away with this. The office editorial staff had since the mid-1960s consisted of an editor-in-chief, an associate editor (or their equivalent), and a handful of editorial assistants who handled proofreading. Production manager John Verpoorten was known for grabbing pages for deadline-stressed books out of the assistants’ hands. He’d reportedly tell them, “You’ll read it when it comes out” (Howe 158). With the company publishing between 40 and 50 titles a month, it was all the staff could manage to get books to the printer on time. Titles in which the scriptwriter doubled as the editor, such as Howard, were probably given the least scrutiny as a matter of course. The lawyers working for Marvel and Cadence Industries (Marvel’s corporate parent) appear to have been largely disengaged from the company’s publishing operations. The situation with the legal personnel was so dysfunctional that Marvel was caught completely unprepared for the changes in the copyright law that took effect in January of 1978. It wasn’t until May of that year that the company’s operational protocols were properly in compliance. No one who was supposed to be paying attention was probably aware of what Gerber was doing.

![htd22a]()

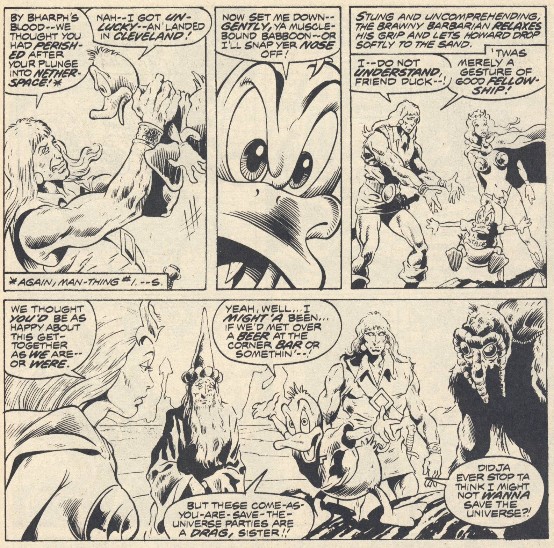

Howard the Duck’s reunion with the Man-Thing cast of characters. From Howard the Duck #22 (March 1978), as reprinted in Essential Howard the Duck, Vol. 1.

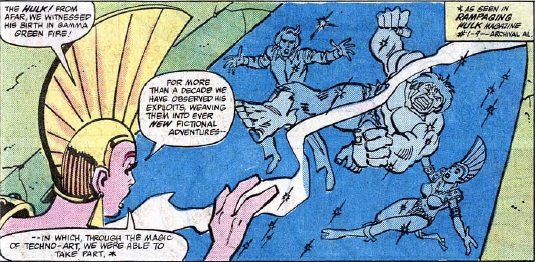

By 1977, Gerber’s anger with the back-issue collector market appears to have subsided. He began to include material that would promote that market to new readers. Specifically, Gerber started highlighting the character’s history before the series. The story in Howard the Duck Annual #1, which shipped to newsstands in the summer of 1977, was drawn by the character’s co-creator Val Mayerik. Next to the splash-page credits, Gerber included the following caption: “Reunited at last! The creative team who hatched the wondrous waterfowl back in (gasp!) 1973!” (Emphases in the original.) And in issues 22 and 23 of the regular series, he reunited Howard with the cast of the 1973 Man-Thing stories. Gerber also included captions that noted the relevant back issues. These were congenial moves to the fans and the collector-market dealers. Apart from sparking interest in those early Howard appearances, Gerber flattered the attention of readers who’d been following his work and Howard from the start.

![htd22b]()

More from Howard’s reunion with the Man-Thing cast.

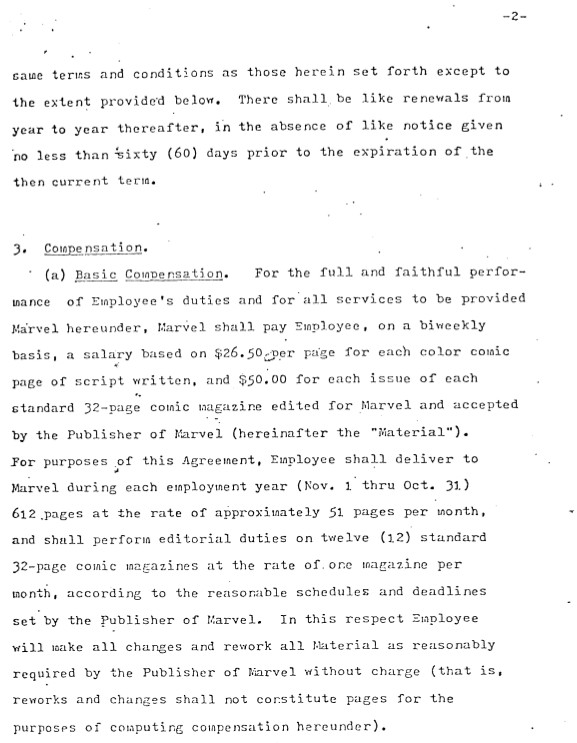

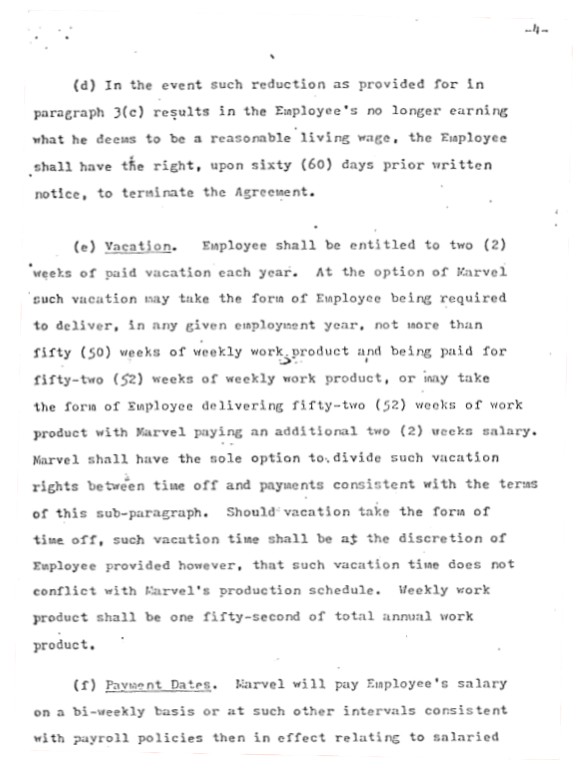

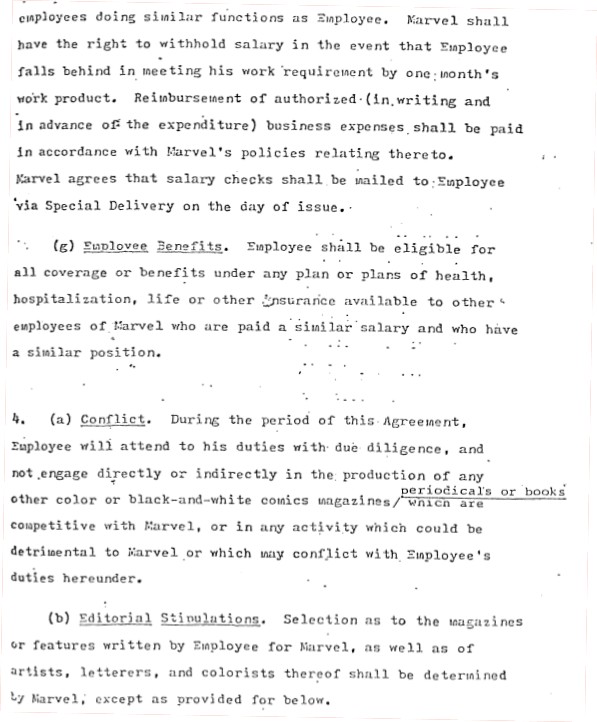

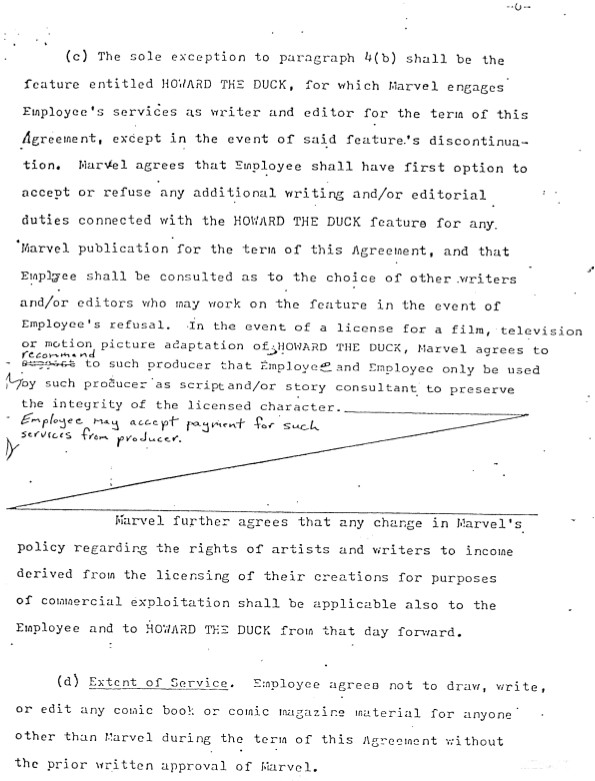

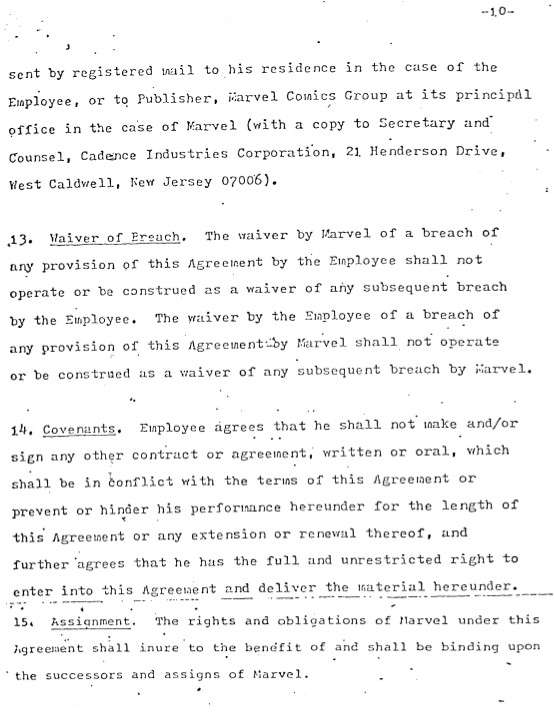

After Gerber scripted a trio of Mister Miracle episodes for DC Comics, Marvel’s largest competitor, Marvel decided it wanted Gerber working exclusively for them. On October 7, 1977, the publisher sent him an employment contract as a comic-book scriptwriter. It also covered his employment as editor of the Howard the Duck comic-book series. Gerber would no longer be a freelancer. His writing and editing work would be solely for Marvel. The contract would pay him, on a bi-weekly basis, a salary totaling $16,818 annually. (This is approximately $65,577 in 2014 dollars.) This income would be in addition to his share of the money from the Howard newspaper strip. Gerber would be expected to script at least 51 comic-book pages per month (the equivalent of three monthly series) and edit 12 standard-size comic books per year. The salary was based on a scriptwriting page-rate of $26.50, and an editing rate of $50 per book. (Adjusted for inflation, these rates would respectively be approximately $103 and $195 in 2014.) Gerber would be compensated at these rates for any work he did beyond his quota. He would be entitled to two weeks of annual paid vacation, and eligibility for enrollment in Marvel’s health, life, and other insurance plans. The term was for one year, and without written notice to the contrary from either Marvel or Gerber, it would automatically renew on an annual basis.

The contract outlined several privileges with Howard the Duck. Gerber would be given right of first refusal for scripting and/or editing duties on Howard projects beyond the monthly comic-book series. If he chose not to work on these projects, he would be consulted as to the choice of writers and/or editors Marvel would employ in his stead. Marvel would recommend and permit him to work for pay as a consultant on any film or television licensing projects. Marvel would also make any policy change about licensing income for writers and artists applicable to Gerber and Howard the day the change went into effect.

It is unknown whether Gerber ever consulted with an agent or attorney about this contract. The clauses regarding the privileges with Howard are troubling when considered against the contract as a whole. The way the contract is written, it appears Gerber would retain his privileges with Howard only as long as he worked for Marvel as a contract employee. Barring a subsequent agreement, if he or Marvel chose to terminate his employment, the privileges with Howard would be terminated along with it. An experienced agent would have most likely recommended Gerber not sign unless these clauses were revised to protect his interest in Howard in the event his employment ended. An attorney would all but certainly have advised him about the termination pitfalls.

Gerber signed the contract on October 27, 1977. To meet his writing quota, he would, in addition to Howard, take over scriptwriting chores on Marvel’s monthly Captain America series. The balance of his work requirement would be taken up with stories for Marvel’s black-and-white magazine line and fill-in efforts in the color comics.

(For a copy of Gerber’s October 7, 1977 Marvel employment contract, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

![James Galton]()

James Galton

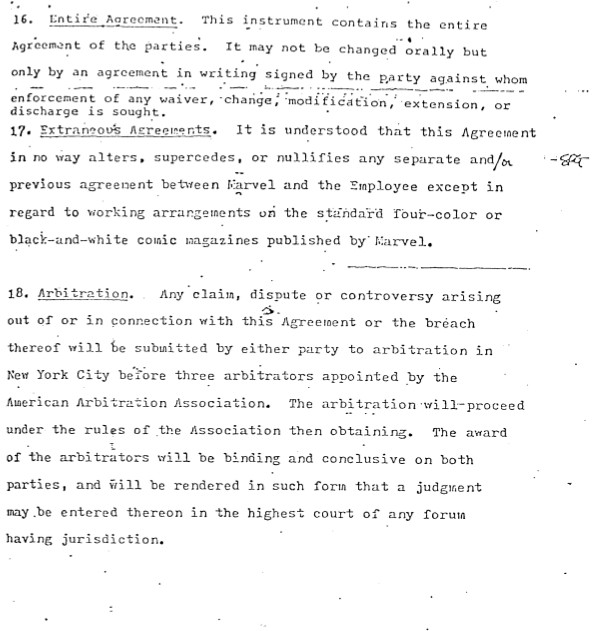

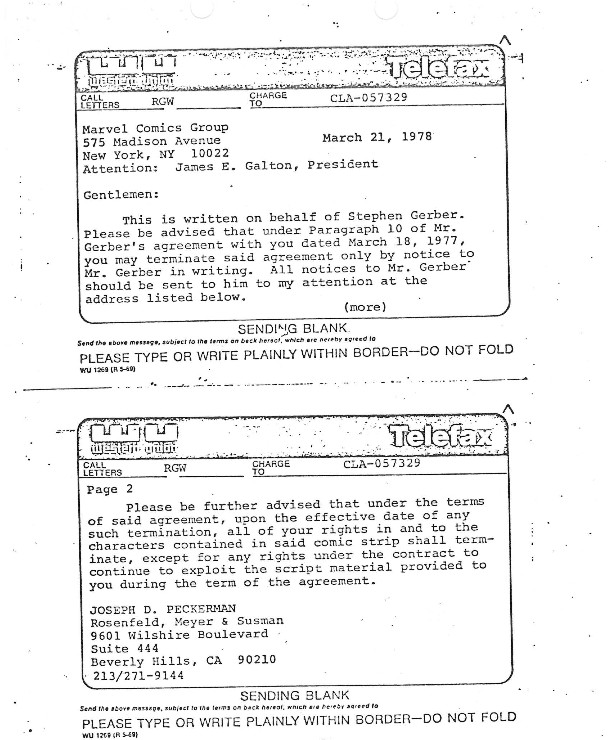

It wasn’t six months before things between Gerber and Marvel went off the rails. In March of 1978, the publisher terminated Gerber’s contract for writing the

Howard the Duck newspaper strip. Gerber was living in Burbank, California at the time, and initially, Marvel publisher Stan Lee attempted to handle the termination over the telephone. Afterward, on March 21, Gerber’s attorney Joseph D. Peckerman sent a telegram to Marvel president James Galton informing him that according to the terms of Gerber’s newspaper-strip contract, the termination was required to be in writing. Galton sent Gerber a formal termination letter on March 28. The reasons Galton gave Gerber for the termination have never been made public. Steve Gerber’s byline last appeared on the newspaper strip with the April 22 daily.

(For a copy of the March 21, 1977 telegram, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

The cause for Gerber’s removal is disputed. Gerber alleged arguments over payment schedules for the artists. Others close to the situation say it was Gerber’s inability to get his work in on a timely basis.

Gerber told John Cooke in 1999:

Marvel wouldn’t pay [Gene Colan] to draw it. [...] Gene and I were supposed to get a percentage of the syndicate’s take for the strip. The problem was, the money came in 90 days, 120 days, six months–I don’t remember how long, exactly–after the strips were published. So, essentially the artist was working for nothing during that time, and no artist can afford to do that. Particularly on a strip he doesn’t own. […] I had a huge fight with Marvel about getting Gene an advance for his work. I wasn’t even asking them to pay Gene, as such–just advance him regular comic book rates against the income from the syndication […] they wouldn’t hear of it. […] Once the arguments started, they escalated very quickly […] They could’ve advanced Gene standard comic book rates to do the Howard newspaper strips. The whole problem would’ve gone away. (66)

However, Colan’s last daily strip was published on October 9, 1977, and his last Sunday appeared on November 6. (For production reasons, the typical Sunday-strip completion schedule runs approximately four to six weeks ahead of that for the dailies.) Colan had left the strip at least five months before Gerber’s termination. He appears to have had a regular income during the time he was working on the strip. According to a sworn declaration filed in federal court in 2011, Colan had also been producing comic-book art for Marvel under an employment contract. It most likely paid him a fixed bi-weekly salary for his comic-book work.

![Gene Colan]()

Gene Colan

In a 2000 interview with Will Allred, Gene Colan had this to say about his time on the strip and his eventual departure:

[...] the scripts didn’t come often enough. Add this to the fact that I was trying to burn the candle at both ends… I was afraid to let go of Marvel because you never know where these things are going to go. I didn’t want to put all my eggs in one basket and do nothing but Howard the Duck [the newspaper strip] and let everything else go. I just couldn’t do both. I actually tried, you know. [...] So, I just kept at it burning both ends. Eventually, I just didn’t have the energy to continue with Howard. Gerber was getting awful fussy and wouldn’t deliver the scripts on time. We were getting hell from the syndicate.

Colan does not appear to have ever addressed Gerber’s claim that the payment schedule posed problems for him, or whether Gerber was fighting to get the payment schedule changed on his behalf.

Val Mayerik, Colan’s immediate successor as artist on the strip, has a similar recollection as Colan. In a 2012 interview with James B. Hudnall, he said:

[…] Steve was also doing the Howard the Duck newspaper strip, and Gene Colan was doing that, was drawing that. And Steve, who was just notoriously late–I don’t know if there was ever anybody in the industry who was ever as late as Steve–had gotten himself so bound up in tardiness that Gene just got fed up, and he couldn’t take it anymore. He just couldn’t draw fast enough to keep compensating for Steve not meeting deadlines. So he dropped out, and Archie Goodwin [Marvel's editor-in-chief in 1977] called me and said, “Do you want to take this over?” And I thought, at the time, I didn’t have a whole lot of work. I had just gotten to New York, and I said, “Yeah, I’ll do it.” […] And I would call Gene [about reference], but Gene was already getting to be an older guy at that point, and he had his own deadlines to worry about, or he’d be off playing cards with his buddies or something. And I’d be talking to his wife, and she got real, real pissed off with me finally. I think she was just letting it out on me because she really wanted to let it out on Steve. “Leave Gene alone. He’s off this thing now. He’s free of Steve Gerber now. Leave him alone.”

Mayerik did not allege any problems with payment in the interview. He erroneously recalled that he left the strip when it was cancelled. He was actually replaced on it by Alan Kupperberg. Kupperberg began drawing the strip with the February 27, 1978 daily, and his first Sunday was published on March 27.

With regard to Gerber’s termination, Tribune & Media Syndicate president Denny Allen told The Village Voice:

[...] there were many cancellations for one very good reason: late delivery. I normally get a strip in 10 weeks before publication. Gerber’s came in on Thursday before the Monday it was supposed to hit the stands. We could barely get it to the papers in time. I ultimately had to tell Steve there wouldn’t be any Howard [emphasis in the original], unless I got a new team to create him [...] the editors I was dealing with at each publication didn’t like the writing either. I thought [Howard] could become a modern Pogo, but they said the public found him too difficult to understand, and the message didn’t come across. (Smith 37)

Marvel’s position was that Gerber was fired from the strip for lateness. Jim Shooter, Archie Goodwin’s successor as editor-in-chief, spoke about the matter to The Comics Journal shortly afterward. The reporting was published in the article “Marvel Fires Gerber.” This is the relevant excerpt:

Tardiness was also said to be the reason for Gerber’s removal from the Howard the Duck strip. According to Shooter, they were “producing strips within six days of their publication dates,” which had in itself caused several papers to drop the strip. The Syndicate had threatened to cancel the strip if a new writer was not chosen, although, according to Shooter, some of the problems stemmed from the difficulties in getting a regular artist [...] It was finally decided that Gerber would have to go. (7)

Marv Wolfman succeeded Gerber as scriptwriter on the newspaper strip. In a July 22, 1978 interview with Kim Thompson, he described the rush schedule he faced upon taking over:

I was told on Thursday I would take over the thing [...] I come into the office early Friday, because I have to go someplace, and Jim Shooter says, “Come in here.” I go into his office; Alan Kupperberg is sitting there. [Shooter] says, “We need three Sundays by Monday.” This is on Friday afternoon. I hadn’t even–now, you have to understand, you put Sundays around your story–I hadn’t even come up with a story. Alan and I did it, somehow, and it’s obvious that the first story suffered from both the deadline problem and the wrong handle for the strip. (51)

Gerber’s reaction to the termination was hostile. In his attorney’s telegram demanding written notice, the following statement was included:

Please be further advised that under the terms of said agreement [Gerber's newspaper-strip contract], upon the effective date of any such termination, all of your [Marvel's] rights in and to the characters contained in said comic strip shall terminate [...]

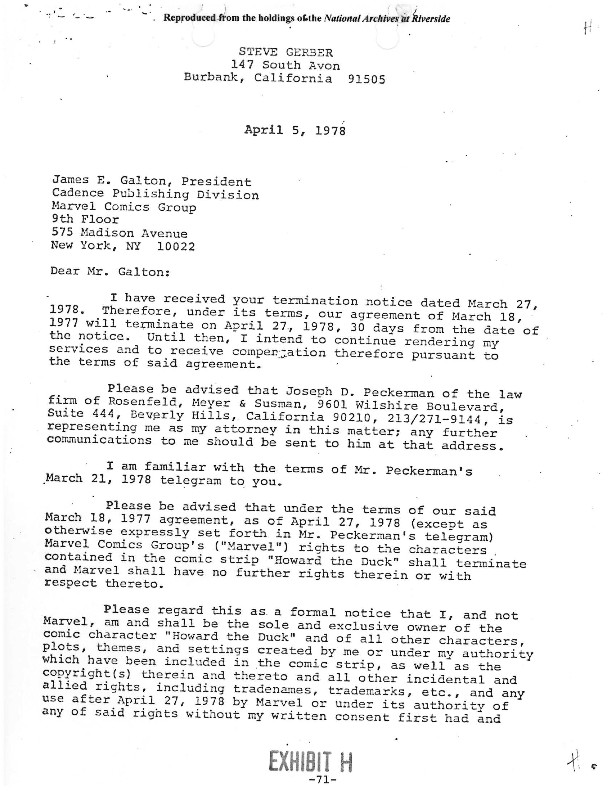

On April 5, 1978, Gerber sent a reply to Galton’s termination letter. In it, he reaffirmed the claims in the telegram, adding:

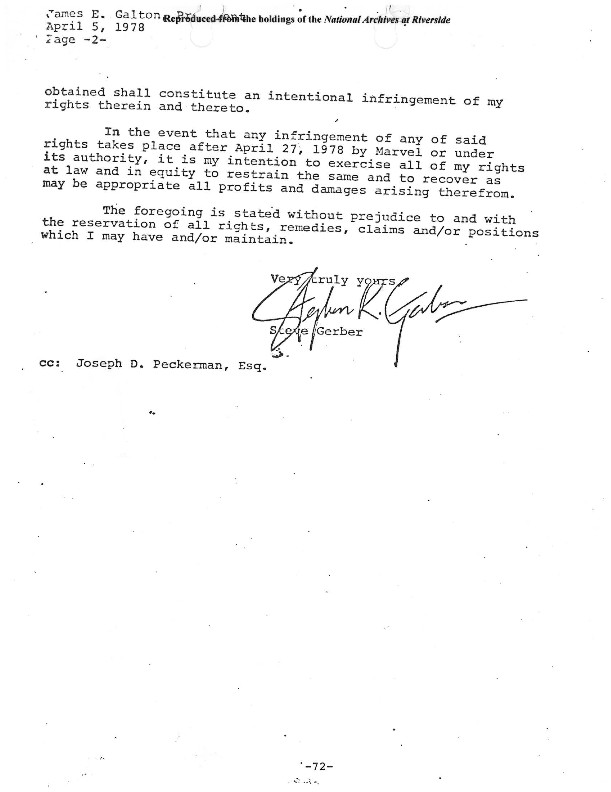

Please regard this as a formal notice that I, and not Marvel, am and shall be the exclusive owner of the comic character “Howard the Duck” and of all other characters, plots, themes, and settings created by me or under my authority which have been included in the comic strip, as well as the copyright(s) therein and thereto and all other incidental and allied rights, including tradenames, trademarks, etc., and any use after April 27, 1978 by Marvel or under its authority of any of said rights without my written consent thereto.

Gerber threatened, in the event of infringement of his alleged rights with Howard, to “exercise all of my rights at law and in equity to restrain the same and recover as may be appropriate all profits and damages arising therefrom.”

(For a copy of Gerber’s April 5, 1978 letter, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

Gerber’s claims in this correspondence are perplexing. There is no language whatsoever in the newspaper-strip contract regarding transfer or reversion of rights in the event of termination or any other circumstance. Judging from the agreement, Marvel’s ownership would seem absolute. Gerber agreed “Marvel shall have all rights of every kind and nature, in and to the material [...]” Marvel appears to have regarded Gerber’s claims and threats as empty bluster. The company never sent a reply.

All Marvel appeared concerned with at this point was ending their relationship with Gerber. His lateness problems weren’t restricted to the newspaper strip. Since becoming a contract scriptwriter, Gerber had been meeting only approximately two-thirds of his 51-page monthly quota. The terms of the contract meant he was getting paid for work he hadn’t done. A blown deadline on Captain America forced a fill-in issue, and Howard the Duck had to be pushed back to bi-monthly status to accommodate Gerber’s output. Gerber also wasn’t making up the balance with his work for Marvel’s magazine line. Jim Shooter took him off Captain America so he could get caught up on other outstanding assignments. It was then that the folderol over the newspaper strip occurred.

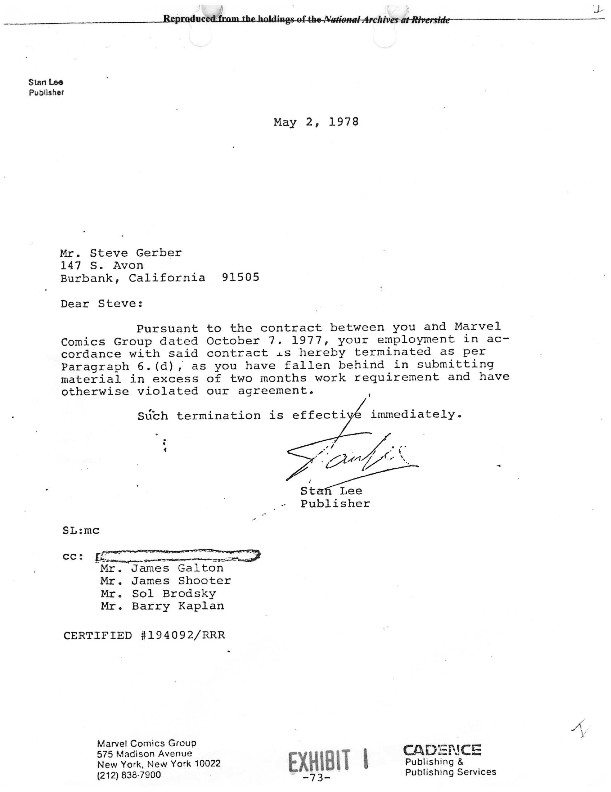

![Stan Lee]()

Stan Lee

On May 2, 1978, Marvel publisher Stan Lee sent Gerber a letter terminating his comic-book scriptwriting and editing contract. The letter’s stated cause for termination was Gerber’s having “fallen behind in submitting material in excess of two months work requirement.” Lee also wrote that Gerber had “otherwise violated” the contract, although he did not provide specifics. However, Gerber’s claiming ownership of Marvel’s intellectual property and threatening legal action was likely seen as engaging in “activity which could be detrimental to Marvel.” The contract explicitly prohibited this. Gerber does not appear to have ever challenged the termination, or disputed the reasons given.

(For a copy of Stan Lee’s May 2, 1978 letter, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

In the article “Marvel Fires Gerber,” Jim Shooter said, “I would not say there was nothing else to it [the termination of the comic-book contract for lateness]; I would just say that we found it advantageous to get out of the contract we were in.” On his website on August 15, 2011, Shooter wrote, “[...] he was threatening to sue Marvel. If you’re threatening to sue your employer, they probably aren’t going to keep paying you so you can pay your lawyers. He was fired. I couldn’t have prevented it if I had tried.”

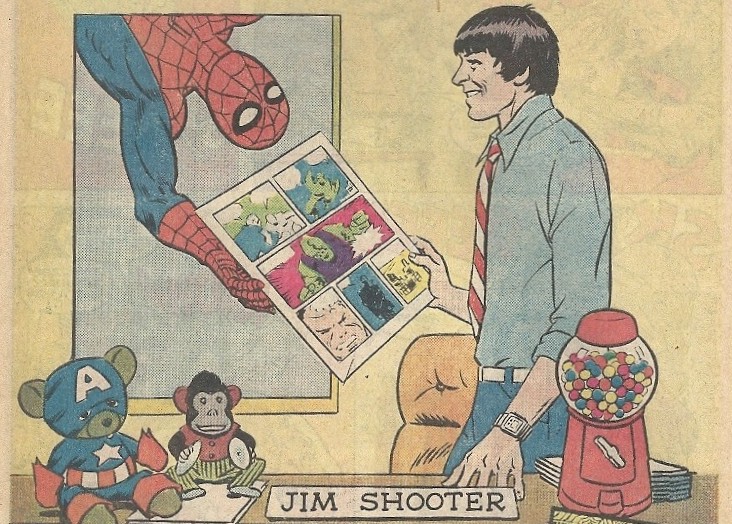

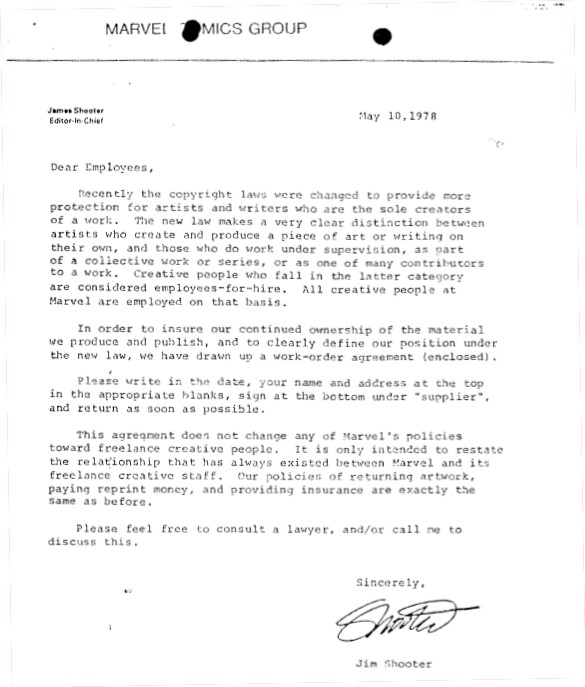

![Jim Shooter]()

Jim Shooter

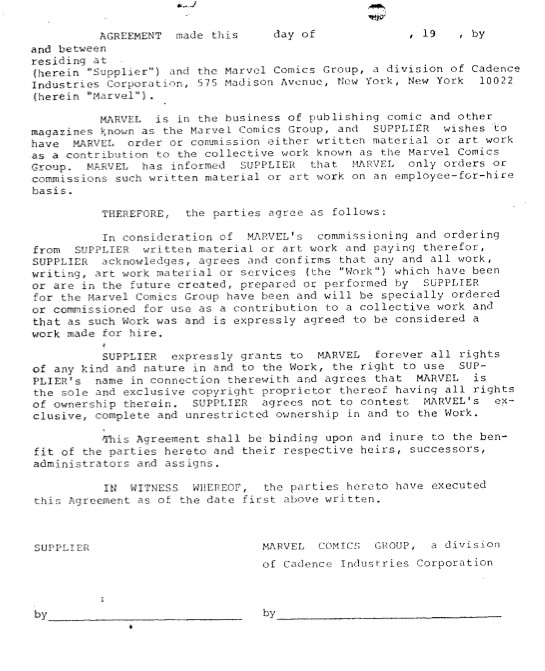

However, Shooter said in 1978 he was still open to employing Gerber on a freelance basis. In “Marvel Fires Gerber,” he called Gerber “one of the best writers in the business.” He further said he would “make any effort to get Steve Gerber type material.” On May 10, 1978, Shooter sent Marvel’s new work-made-for-hire contract to the writers and artists in Marvel’s freelance contributor pool. The provisions of the 1976 Copyright Act had gone into effect that January, and one of them was the new requirement that freelance work-made-for-hire relationships be acknowledged in writing. Gerber was among those who received the contract in the mailing. He chose not to sign it. That and the termination of his employment contract meant he could no longer be assigned new work on Marvel’s company-owned publications. For the time being, Marvel would no longer commission new material from Steve Gerber.

(For copies of Marvel’s 1978 work-made-for-hire contract and Jim Shooter’s accompanying cover letter, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

On May 26, Gerber issued a statement to The Comics Journal about his separation from Marvel. It was published in the preface to a multi-page interview with Gerber by The Comics Journal editor Gary Groth. The statement read in part:

I was dismissed from the HOWARD THE DUCK newspaper strip in a manner which violated the terms of my written agreement. Marvel was advised that I was contemplating legal action which would likely result in my ownership of the HOWARD THE DUCK character and all rights therein. As a consequence of the notice given Marvel by my lawyers, the company chose to terminate my contract on the comics as well. Marvel’s action was not unanticipated, and my only regret is that, for a while at least, the Duck and I will be travelling separate paths. (26)

Gerber did not discuss his legal and business conflicts with Marvel in the interview. As for the statement itself, Gerber has never elaborated on how he was dismissed “in a manner which violated the terms of my written agreement.” From what is known, there doesn’t appear to have been any violation. The only thing that might remotely qualify is Stan Lee’s attempt to terminate the contract over the telephone.

As for what happened next between Gerber and Marvel, there wasn’t much of anything for quite some time. Gerber’s claims and threats were proving empty. The business and legal correspondence related to Howard looked to have ended with the termination of Gerber’s comic-book contract. Things proceeded as they had been, although without Gerber. Marvel continued to produce the newspaper strip with Marv Wolfman and Alan Kupperberg. The comic books also continued. The first two issues sent to press after the termination featured inventory stories plotted by Wolfman and Mark Evanier. Bill Mantlo then took over as the new scriptwriter, with Gene Colan returning as penciller. They did two new issues of the standard-size color comic book series, with the second reaching newsstands in February of 1979. The feature then went on hiatus for about six months.![22820]()

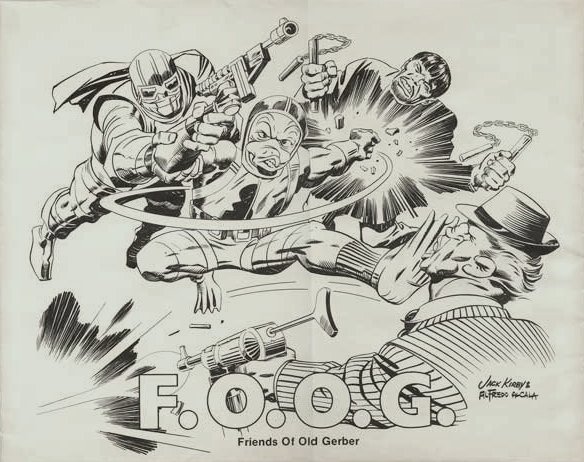

Later in 1979, a new series was launched as part of the Marvel magazine line, with painted covers, black-and-white interiors, and a larger trim size. The format, which was subject to more relaxed content restrictions than the color comics, was intended to appeal to older readers. The first issue (cover at right) had an October cover date and reached newsstands in August. Mantlo continued as scriptwriter, with Colan pencilling most of the stories.

There is no indication that Steve Gerber ever received any monetary compensation for this or the other publications. He doesn’t appear to have even complained about it.

Sometime in 1978, Disney seems to have taken notice that the most significant element of the Howard redesign was not being followed. The character was still not wearing pants. Negotiations were reopened, and in late 1979, Howard appeared to have been permanently trousered. According to Steven Grant’s article on the redesign, the second agreement codifying the redesign doubled the original’s length from four to eight pages (28). It was signed in 1980.

The non-Gerber Howard the Duck made almost no one happy. In The Village Voice, Gerber called the Wolfman/Kupperberg newspaper strips “downright horrible,” adding that the feature was “lobotomized, devoid of substance, and turned into a simple-minded parody” (Smith 37). According to Wolfman, Marvel publisher Stan Lee told him, “The Duck strip is really the worst thing I’ve ever seen” (Thompson 51). In an August 11, 2011 website post, Jim Shooter confirmed Lee’s low opinion of the Wolfman/Kupperberg material: “Suffice to say he hated it.” Mantlo’s stories weren’t well received, either. In a 1980 interview with Gary Groth, Shooter indicated he was especially put off by Mantlo’s shift from Gerber’s absurdist tone to partisan political polemic. It led him to ultimately remove Mantlo from the feature. Artist Stephen Bissette summed up the general feeling about the non-Gerber material years later when he said, “Howard the Duck has not made any sense without Steve Gerber” (Creators 105). In a contemporaneous essay, he wrote:

Howard the Duck was Steve Gerber, a direct, vital extension of his very self [...] Cut off from his creator, Howard is a meaningless, empty corporate-owned image, only as good as the creators employed to breathe life into him and none of those who followed in Gerber’s footsteps ever came close [emphasis in the original]. (Bissette 67-68)

The character’s commercial appeal was dwindling, too. The newspaper strip lasted just six months without Gerber at the helm; the final episode was published on October 29, 1978. The black-and-white comics magazine ran for only nine issues before it was cancelled. Low sales were presumably the reason. The final issue, cover-dated March 1981, shipped to newsstands that January. Less than three years after the forced separation from his principal creator, Howard the Duck sputtered into publishing oblivion.

As for Gerber, he seemed without direction at first. He wrapped up his obligations to Marvel with a “Lilith” story that was published in Marvel Preview #16 (Fall 1978). In his The Comics Journal interview, he mentioned that he was working on a three-part Dr. Fate story for DC (40-41). However, no story by Gerber featuring Dr. Fate saw print in the late ’70s, and it is unknown if Gerber ever completed it. (In 1982, DC published a four-part Dr. Fate story written by Gerber and Martin Pasko, but there is no indication whether this was the same project or a different one.) Gerber’s close friend Mark Evanier was packaging a line of comics for Marvel featuring the Hanna-Barbera animation characters. Gerber scripted a handful of stories for them under the pseudonym Reg Everbest. Evanier also had contacts in the TV-animation industry, and he got Gerber work at Ruby-Spears Productions.

It was the beginning of a second career. Gerber’s first TV writing assignment was on The Plastic Man Comedy/Adventure Show. Shortly afterward, he successfully pitched the Thundarr the Barbarian series to studio owners Joe Ruby and Ken Spears. The program, featuring design work by the celebrated comic-book cartoonists Alex Toth and Jack Kirby, debuted on the ABC network in the fall of 1980. Gerber wrote the series’ bible, served as the story editor, and was among the credited writers for every episode. The program quickly developed a cult following, and it has sustained interest to this day. Over the next seven years, Gerber worked as a writer and story editor for several animated TV series, including Dungeons & Dragons, G. I. Joe, and Transformers.

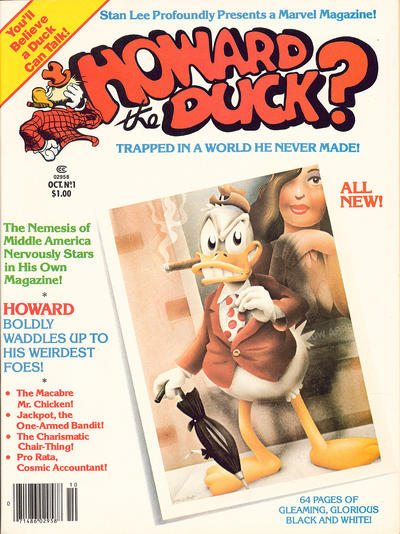

![Stewart the rat Cover]() Gerber hadn’t entirely turned his back on the comic-book field. In 1980, Eclipse Enterprises published Stewart the Rat, a satirical graphic novel featuring a rodent character in the same vein as Howard. With Gerber’s claims and threats over Howard apparently in the past, Marvel didn’t seem to hold any ill will. Stewart was pencilled by Gene Colan and inked by Tom Palmer, both of whom were under exclusive employment contracts to Marvel. Marvel gave them permission to work on the project. The book was distributed only to comic-book specialty stores, which carried publications on a non-returnable basis. Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney was not able to provide information about sales in time for this article’s publication, but indications are that they were modest and below expectations. There appears to have been only one printing, and Eclipse still had copies available for purchase through mail order over a decade later. Gerber, who fully owned the intellectual-property rights to Stewart, never revisited the character.

Gerber hadn’t entirely turned his back on the comic-book field. In 1980, Eclipse Enterprises published Stewart the Rat, a satirical graphic novel featuring a rodent character in the same vein as Howard. With Gerber’s claims and threats over Howard apparently in the past, Marvel didn’t seem to hold any ill will. Stewart was pencilled by Gene Colan and inked by Tom Palmer, both of whom were under exclusive employment contracts to Marvel. Marvel gave them permission to work on the project. The book was distributed only to comic-book specialty stores, which carried publications on a non-returnable basis. Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney was not able to provide information about sales in time for this article’s publication, but indications are that they were modest and below expectations. There appears to have been only one printing, and Eclipse still had copies available for purchase through mail order over a decade later. Gerber, who fully owned the intellectual-property rights to Stewart, never revisited the character.

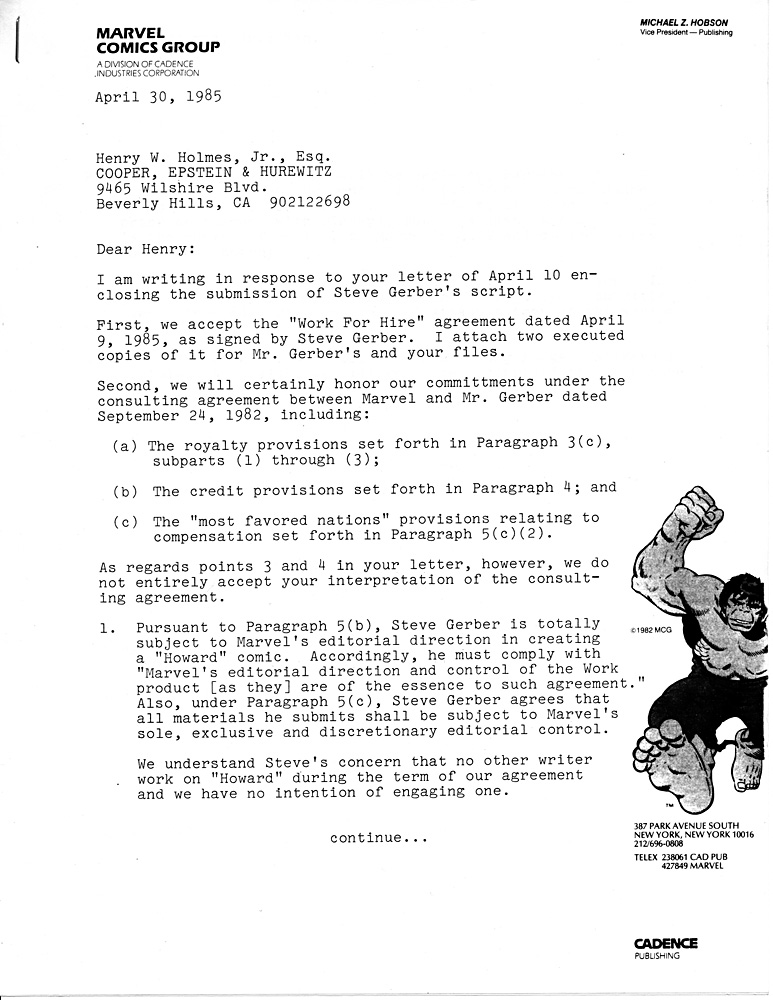

As for Howard, he may have become moribund as a publishing property, but there was interest in him elsewhere in the media world. The Los Angeles-based Selluloid Productions took particular notice. Sometime in 1980, Marvel entered into negotiations with Selluloid to license the character for use in film, radio, and television. On September 1, 1980, the two companies signed an agreement giving Selluloid production and distribution rights for a Howard the Duck radio serial. Selluloid was also granted a one-year option for a live-action film featuring the character. Production on the radio serial, which starred Jim Belushi as Howard, began immediately. The show was intended for distribution to FM album-oriented-rock stations. Around this time, Marvel Productions, a Los Angeles-area animation studio owned by Marvel Comics’ corporate parent Cadence Industries, began putting together story and art materials for a Howard the Duck animated TV-series proposal.

![Belushi]()

From left to right, producer Lee Arnold, actor Jim Belushi, and director Steve Lushbaugh recording the pilot for the Howard the Duck radio serial. Photograph by Alan Penchartsky. From the October 4, 1980 issue of Billboard magazine.

In a December 24, 1980 sworn declaration, Steve Gerber indicated that he learned of the licensing negotiations between Marvel and Selluloid several months before they were finalized. He stated he contacted Marvel about the matter, although whether the contact or contacts were verbal or written was not clear. He asserted in these communications that only he, not Marvel, had the right to license or sell Howard the Duck and Howard the Duck stories. Gerber also said he offered to license Marvel the character and stories, but that Marvel refused to negotiate or agree to anything.

(For a copy of Steve Gerber’s December 24, 1980 declaration, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

It had been more than two years since Marvel publisher Stan Lee had terminated Gerber’s employment at Marvel. Gerber’s claims and threats regarding ownership of Howard the Duck appeared to have ended with Lee’s termination letter. But at this point, with the possibility of film and broadcast-media treatments of Howard on the horizon, Gerber decided to renew the fight.

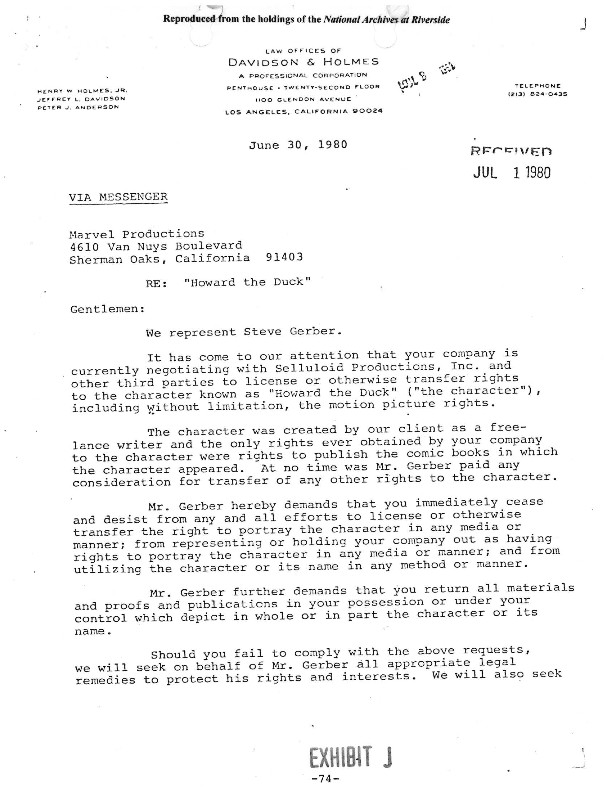

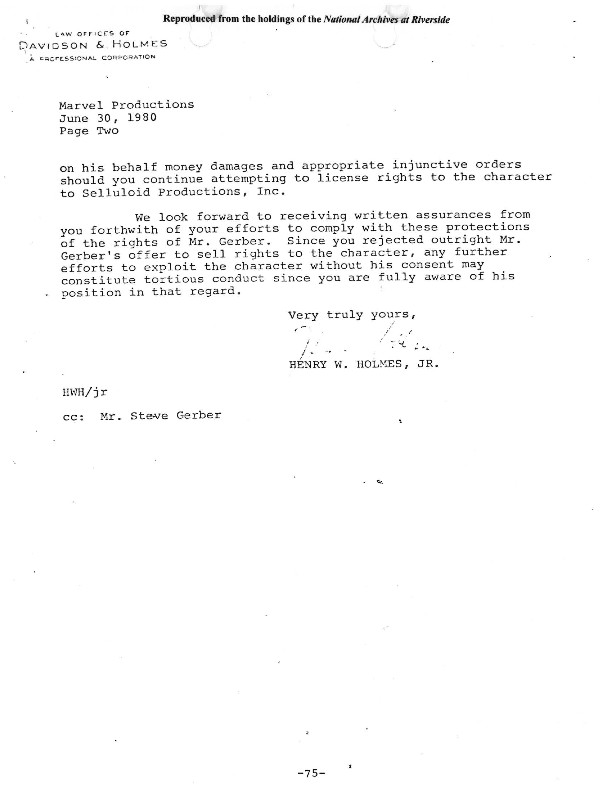

After Marvel’s latest rebuff, Gerber retained the services of attorney Henry W. Holmes, Jr. and the law firm Davidson & Holmes. (Holmes is probably best known for representing tennis icon Billie Jean King, boxing champion George Foreman, and science-fiction author Harlan Ellison.) On June 30, 1980, Holmes sent a letter on Gerber’s behalf to Marvel Productions. The letter demanded that Marvel Comics cease and desist all licensing negotiations with Selluloid. It was claimed that Gerber had never sold any rights to Marvel with regard to Howard the Duck beyond the rights to publish comic books featuring the character. The letter included the demand that Marvel return to Gerber “all materials and proofs and publications in your possession which depict in whole or in part the character or its name.” Holmes threatened legal action with reference to punitive damages if Marvel did not comply. Marvel does not appear to have responded to the letter.

(For a copy of Henry Holmes’ June 30, 1980 letter, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

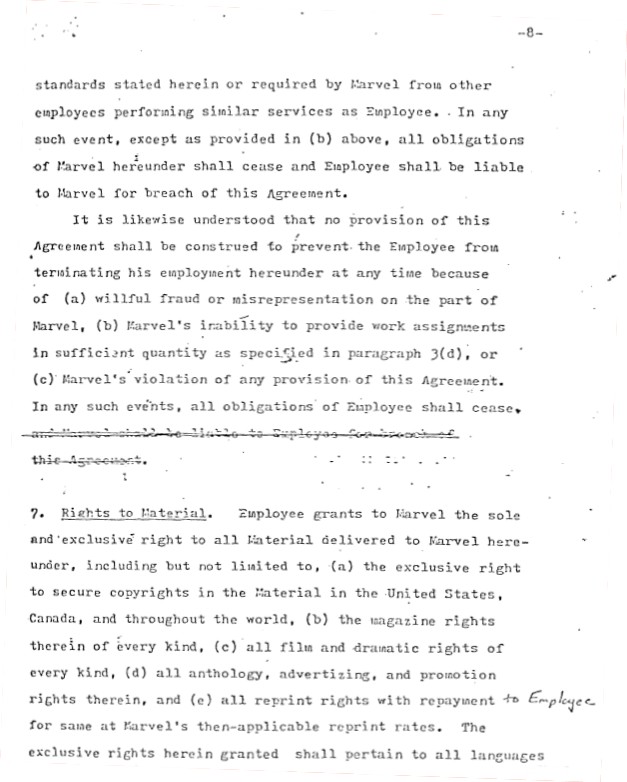

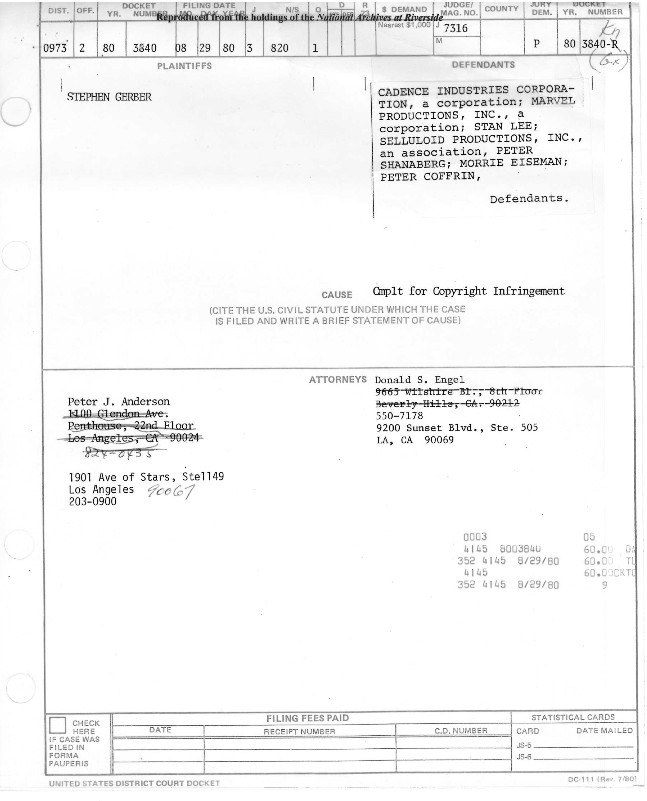

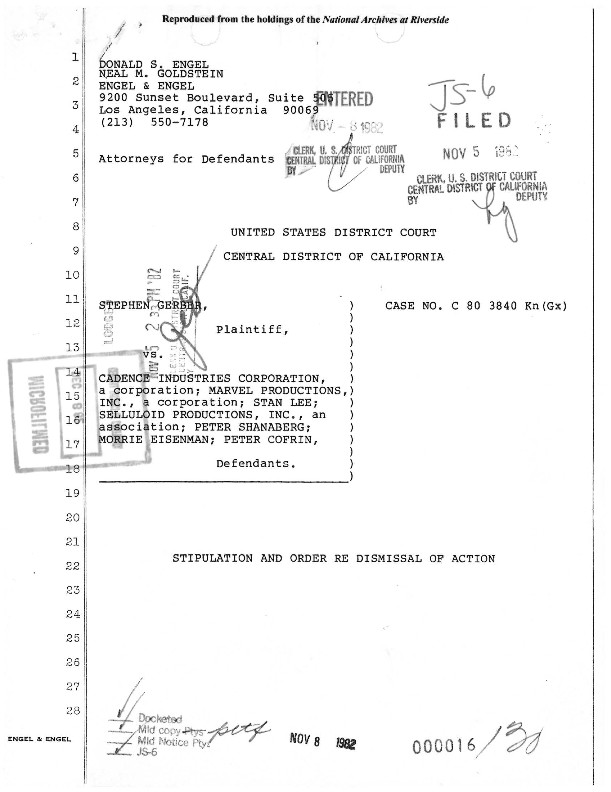

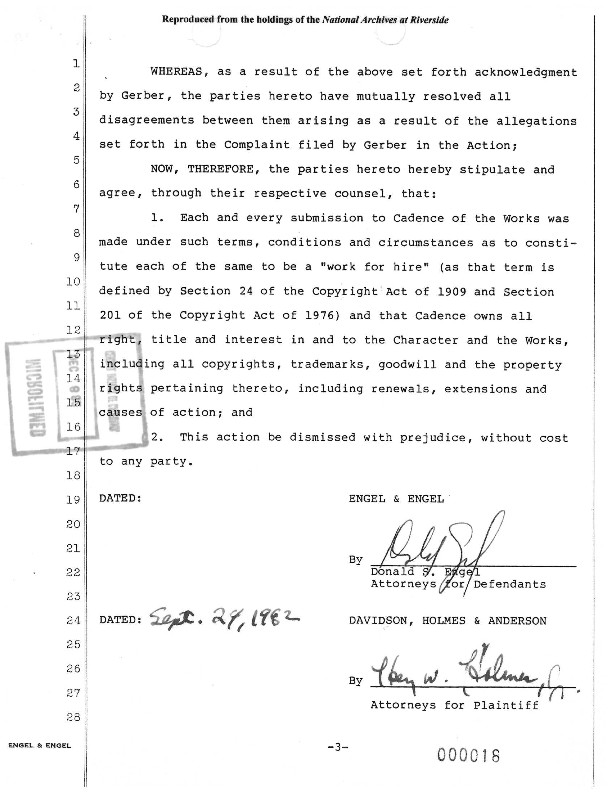

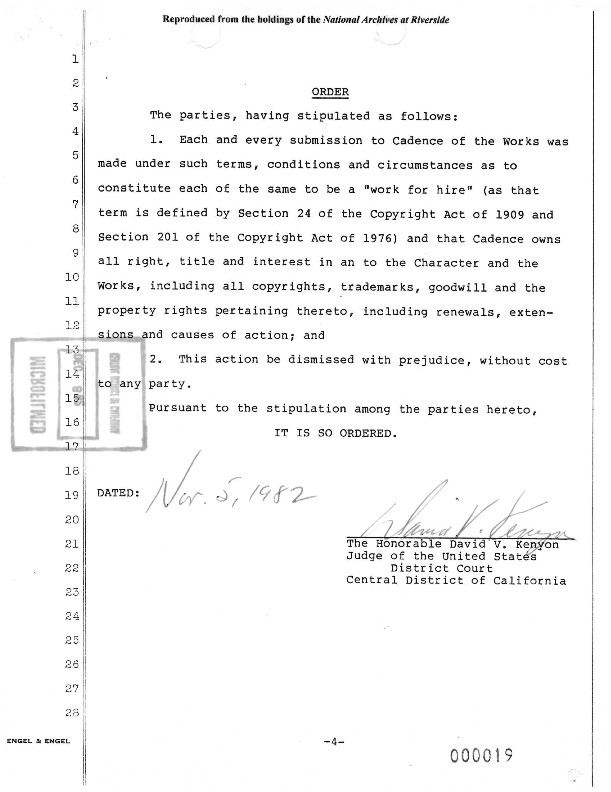

On August 29, 1980, Holmes filed suit on Gerber’s behalf in U. S. District Court, Central District of California. The defendants were the Cadence Industries Corporation, Marvel Productions, Inc., Marvel publisher Stan Lee, Selluloid Productions, Inc., and Selluloid principals Peter Shanaberg, Morrie Eiseman, and Peter Coffrin. The stated cause of action was copyright infringement. There were six claims for relief.

The first claim asserted that any license agreed to between Marvel and Selluloid with regard to Howard the Duck constituted infringement of Gerber’s intellectual-property rights.

The second claim demanded the following: (1) any agreement between Marvel and Selluloid or any other licensee regarding Howard be declared invalid; (2) any profits or benefits derived from those agreements be turned over to Gerber; (3) Marvel was to be required to assign and convey to Gerber “the copyright and all rights and interest” with regard to Howard and the related comic-book stories; and (4) all prior agreements relating to copyright assignment and conveyance between Marvel and Gerber were to be nullified.

The third and fourth claims alleged, respectively, unfair competition and conversion. The fifth accused Marvel of breach of implied contract by seeking to license Howard without Gerber’s consent.

The sixth accused Marvel and Stan Lee of “Breach of Trust and Confidence.” Marvel and Lee were alleged to have deliberately swindled Gerber out of the official copyrights for Howard and the related stories.

The complaint demanded, from each of the defendants, compensatory damages of not less than $250,000, and punitive damages of not less than $2.5 million. It also demanded a jury trial. According to the court docket, all defendants had been served with the complaint by October 16, 1980.

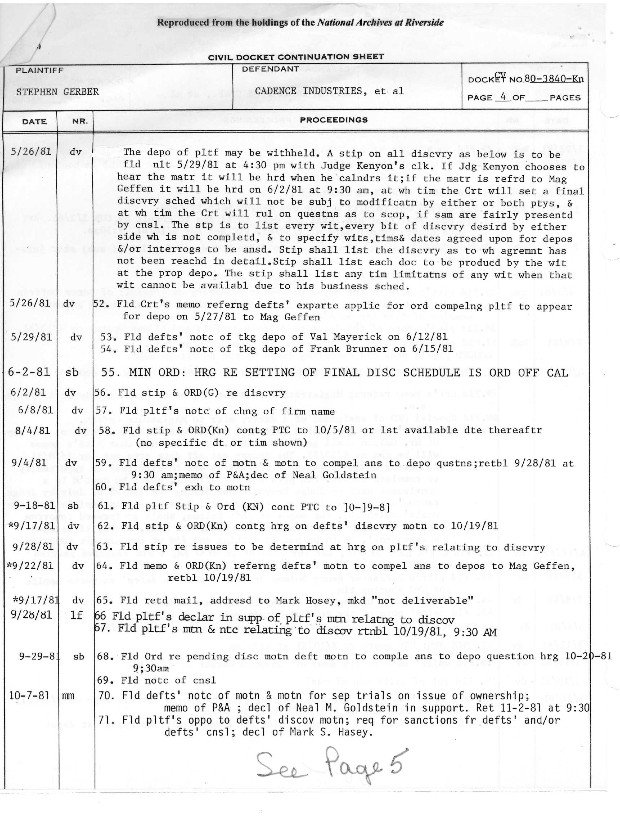

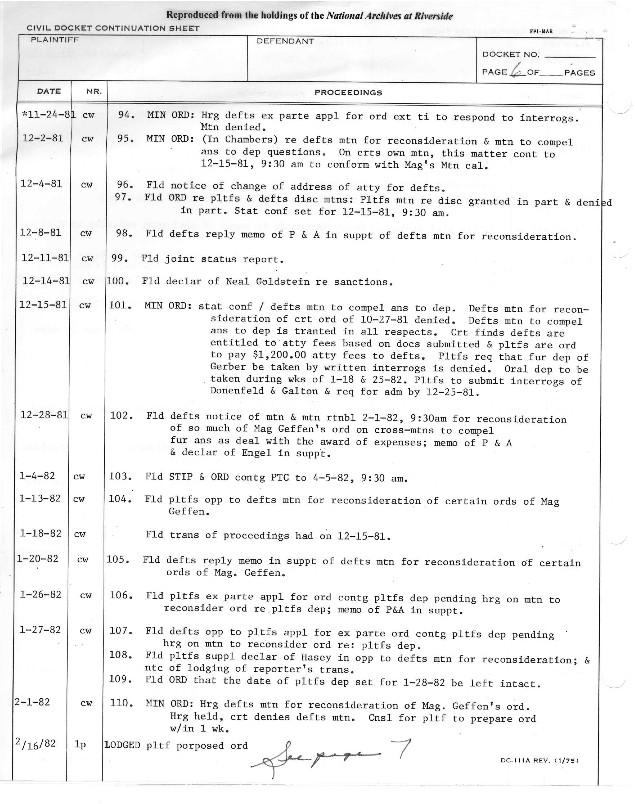

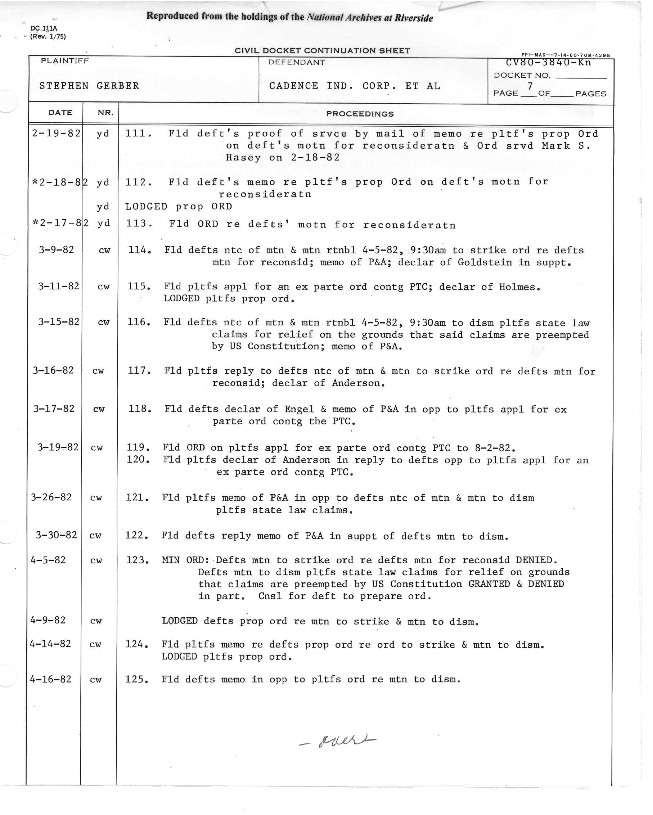

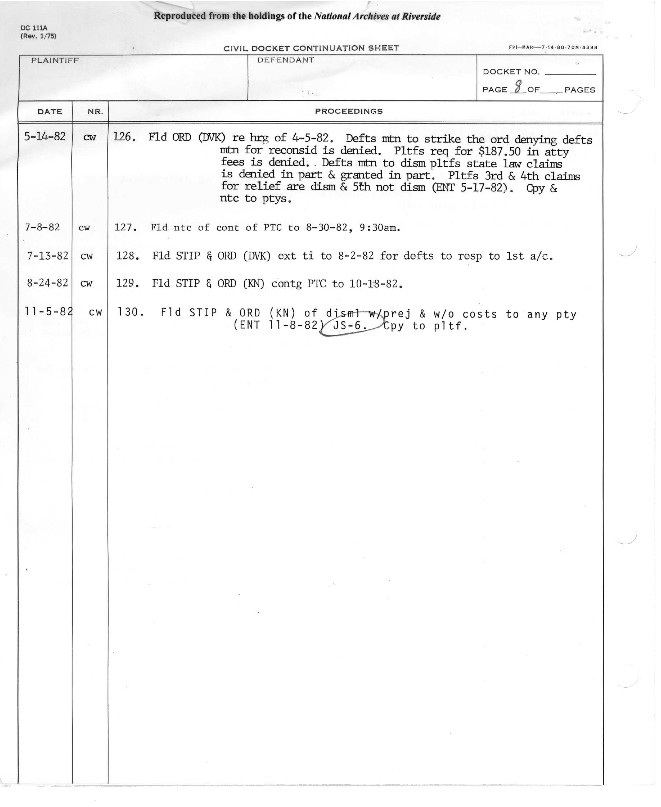

(For copies of the court docket and the lawsuit complaint, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

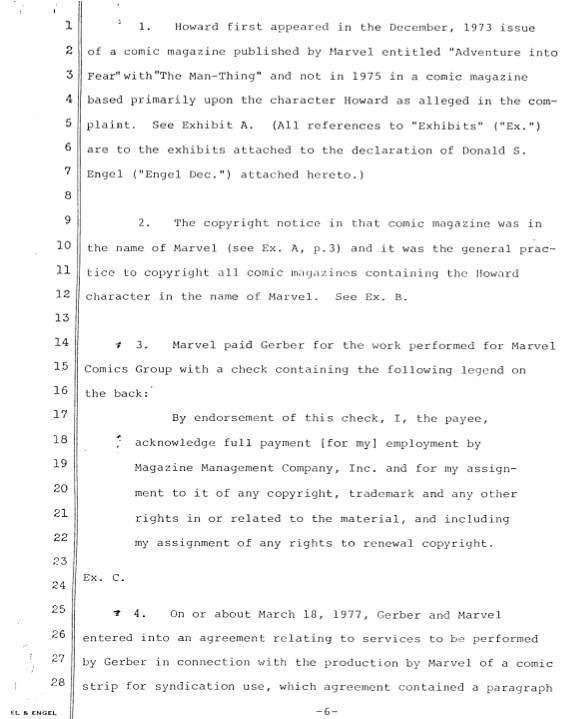

On November 14, 1980, Donald S. Engel, a Los Angeles attorney representing Lee, Selluloid, and the Selluloid principals Shanaberg, Eiseman, and Coffrin, filed a motion to dismiss the suit on jurisdictional grounds. (The motion is dated November 12.) In the accompanying memorandum of points, Engel argued the suit was not about copyright infringement, which is under federal-court jurisdiction. Rather, Engel wrote, it was “a cause of action to determine contract rights and title in and to a copyright.” Gerber and Marvel were, according to Engel, in disagreement over the interpretation of his contractual relationship with the company. Engel claimed Gerber was effectively petitioning the court to transfer ownership of the Howard copyrights to him, which he argued the court lacked jurisdiction to do. In support of his argument, Engel cited Gerber’s Marvel contracts, numerous court precedents, and the fact that Marvel, not Gerber, held the registered copyrights to the Howard material. Pointing to the letters between Gerber and Marvel concerning Gerber’s contract terminations, Engel wrote, “It is apparent from this correspondence that the dispute between Marvel and Gerber can be stated in one sentence: Who owns the rights to the character Howard?” Numerous exhibits were filed as part of the motion, including Gerber’s Marvel contracts and all but one piece of the termination correspondence.

Engel made no mention of Gerber’s acknowledgement in the 1976 pin-back button licensing agreement that Howard was Marvel’s exclusive property. Nor did he mention that Gerber promised in the contract to never challenge Marvel’s proprietary rights.

(For a copy of Donald S. Engel’s November 12, 1980 Motion to Dismiss and Memorandum of Points, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

Gerber and Holmes filed their respective responses to the motion to dismiss on December 24, 1980. Gerber’s took the form of a sworn declaration that purportedly outlined his view of the dispute. Holmes’ brief countered Engel’s legal arguments regarding jurisdiction.

(For copies of Steve Gerber’s declaration and Henry Holmes’ brief in reply to the motion to dismiss, both dated December 24, 1980, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

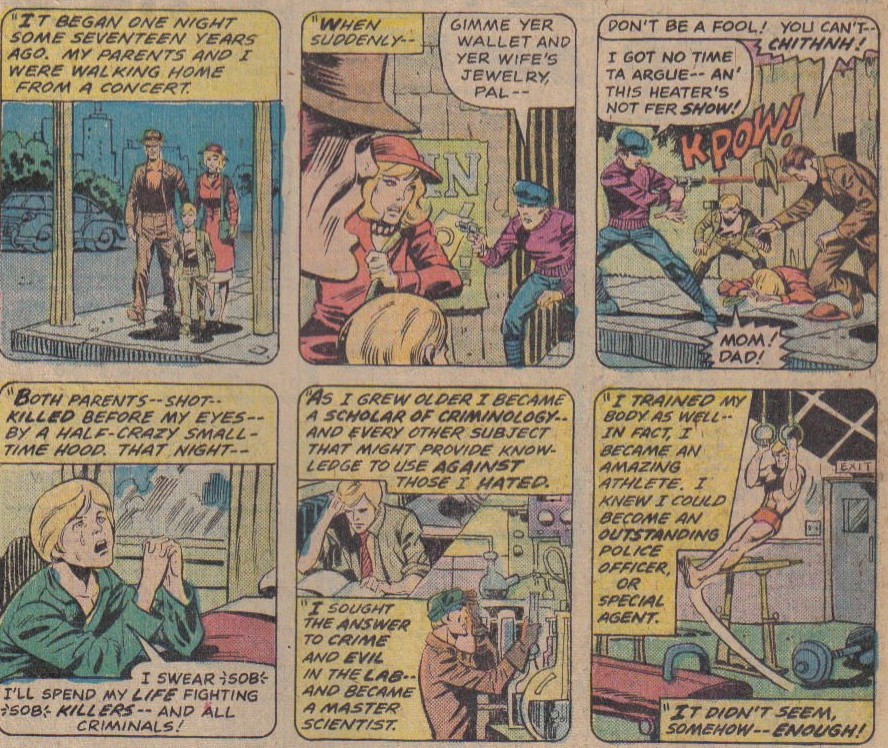

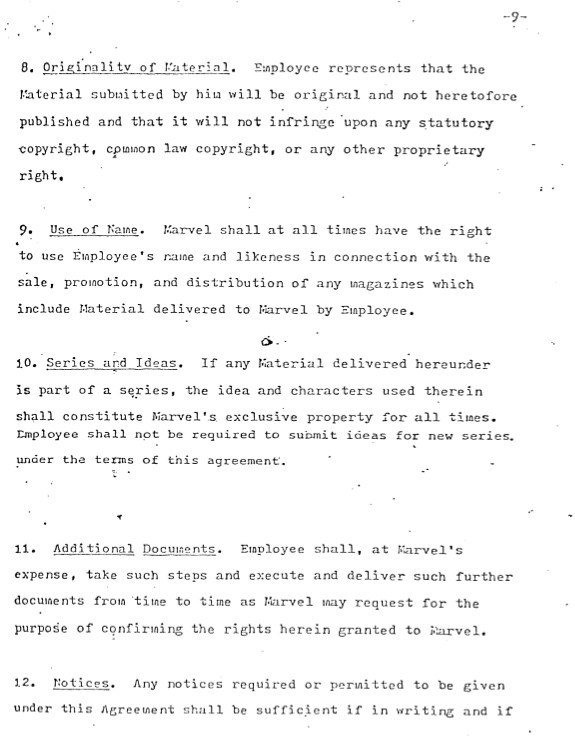

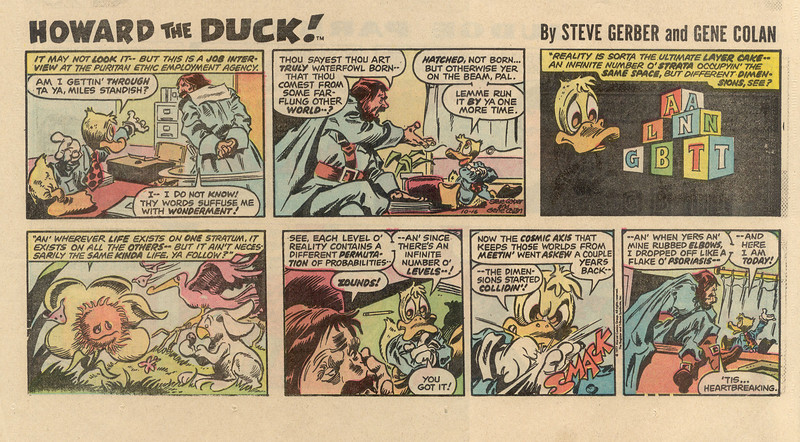

Gerber began his declaration by claiming that since he created Howard as an independent contractor, he could not be considered Marvel’s employee when doing so. In an apparent effort to counter the point that Howard was created in the context of a company assignment, he asserted that the Howard who played a supporting role in the two 1973 Man-Thing episodes was not the same character who appeared in the Howard the Duck comic-book series. The Howard of those 1973 stories was a “minor walk on character,” “a mere proto-type” of the one in the Howard series, “killed off,” and “for all purposes ended [...]“. The Howard that began appearing in 1975 was a “new character,” “much more sophisticated,” and “entirely different” from the one that originally appeared in Adventure into Fear #19.

Gerber did not explain how he reconciled this view of the Howard character(s) with his statements in interviews, or the material in the Marvel Treasury Edition, Howard the Duck Annual #1, and, especially, Howard the Duck #22 and 23.

As an exhibit, Donald S. Engel had submitted a copy of the June 1, 1973 check that ostensibly paid Gerber for the scripting of the Adventure into Fear episode introducing Howard. Gerber attempted to discredit it by erroneously claiming that the cover date of December 1973 was when the publication went on sale. Gerber noted the standard lead time of scripting a Marvel color comic was three to four months ahead of publication. As such, this meant the episode could not have been written before June 1. He claimed it would have been written in August or September (the actual on-sale month). Gerber had nothing to say about the back-of-the-check rights acknowledgement.

Gerber then proceeded to directly discuss the copyright and ownership issues. He asserted that with Howard, “Marvel was granted only a limited license to publish, nothing more.” “Marvel Comics,” according to Gerber in the declaration, “did not ask me, nor did I agree, to assign or transfer rights to use or depict Howard or the Howard stories in any other medium, means, or matter. All of such rights were reserved by me.” Gerber wrote that he was told by Stan Lee and Marvel president James Galton “in substance” that his rights and interest in Howard were being protected for him by Marvel. He added that Galton told him, again “in substance,” that this protection made it unnecessary to put the copyrights in Gerber’s name. He also wrote that Lee and Galton told him no outside use of Howard would be made without his consent and participation.

Gerber went on to assert that “Marvel Comics did not even believe it had rights to Howard or the Howard stories, other than publication of comic magazines.” In support of this, he pointed to his newspaper-strip contract, which he said “clearly demonstrated” that “Marvel sought out and obtained his consent” with non-comic-book projects. Gerber went on to assert that that the termination of the newspaper-strip contract meant that the “limited license of rights” that he had granted Marvel was terminated as well. When it came to proof that the “limited license” was terminated, Gerber mentioned only his claims in the termination correspondence, and that the strip was eventually cancelled. As for his comic-book employment contract, he said it “pertained only to new creations” that he wrote during its term. It did not “relate to characters and stories” Gerber had created beforehand.

Gerber did not address how he could make such claims given that (1) the newspaper-strip contract contained no language whatsoever about obtaining his “consent”; (2) the contract characterized Gerber’s involvement with the strip as “services you will perform” and similar terms; and (3) it had Gerber “agree that Marvel shall have all rights of every kind and nature, in and to the Material [...]” He also did not discuss why, if what he said was accurate, the contract included no language of any kind that could be interpreted as referring to any license, “limited” or otherwise, or why there was no provision whatsoever for transfer or reversion of rights or ownership.

Gerber addressed the licensing agreement for the “Vote Howard” pin-back buttons. He started off by claiming it was “irrelevant” to the dispute and “not a grant [...] to Marvel Comics of any right to Howard or the Howard stories.” He effectively claimed he had the right to produce the buttons without Marvel’s permission. In describing the reasons he sought the agreement with Marvel, he wrote:

I felt that lending Marvel Comics’ name to the button [the buttons featured a Marvel copyright notice on the front], using the button design as an element of comic book stories, and obtaining free national advertising from Marvel Comics in its comic magazines would enhance sales of the button.

Gerber went on to say he “was motivated to pay a small royalty partially out of concern over Marvel Comics causing a dispute over use of its corporate name in connection with the button.”

Gerber did not discuss why his signing the licensing agreement should not be seen as acceptance that Howard was already Marvel’s property, particularly since it included a clause in which Gerber “acknowledges” that all intellectual-property rights to Howard “belong exclusively to” Marvel. He also did not discuss his contractual promise to never challenge Marvel’s proprietary rights to the character.

Gerber did not allege, as he had in his 1978 letter to The Comics Journal, that Marvel had removed him from the strip “in a manner which violated the terms of my written agreement.” He suggested that he was planning to terminate the newspaper-strip contract himself when he received James Galton’s March 27, 1978 letter.

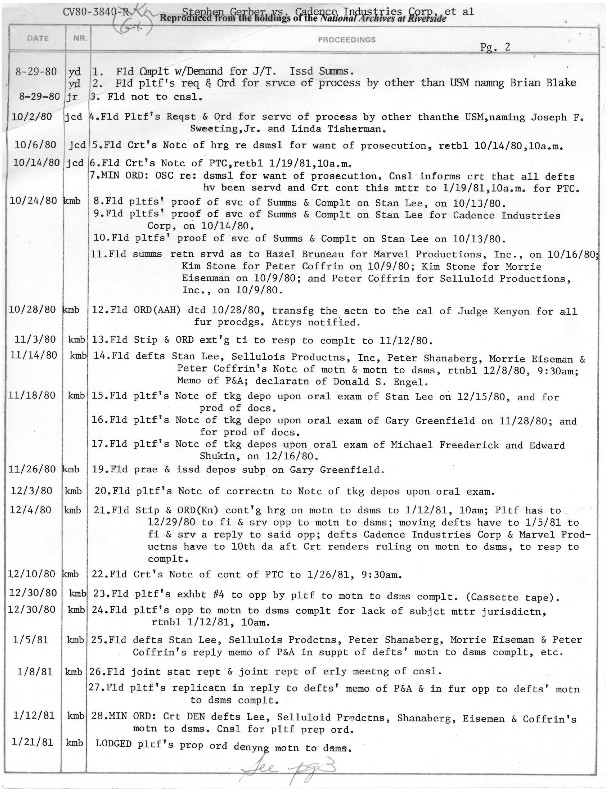

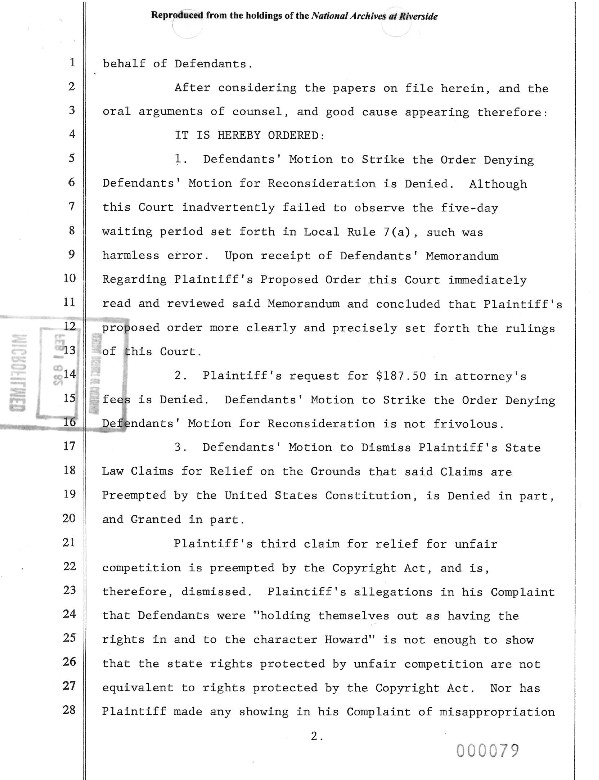

On January 12, 1981, Judge David Kenyon denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss on jurisdictional grounds. Three weeks later, on February 2, the defendants filed their official answer to the lawsuit complaint. According to the filing, Donald S. Engel and his firm Engel & Engel were now representing Cadence Industries and Marvel Productions as well as the other five defendants.

Apart from some minor factual points (for example, “Defendant Lee is a resident of Los Angeles County”), Engel denied the claims in Gerber’s complaint in every particular. He named eight affirmative defenses.

The first defense stated that, with Gerber’s claims for relief, part of the second, and all of the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth ones were based on common law and California statute. Engel asserted that these claims were preempted by the U. S. Copyright Act of 1976 and should be dismissed.

With the second defense, Engel stated that Gerber was at all relevant times producing material on a work-made-for-hire basis. The third defense stated that Gerber assigned all relevant intellectual-property rights to Marvel. The fourth asserted that the actions of the defendants at issue constituted the proper exercise of their rights in and to the copyrights of the material.

According to the fifth defense, Gerber was barred from seeking relief due to his prior recognition of Marvel’s ownership of the intellectual-property rights to Howard the Duck.

The sixth defense asserted that Gerber was further barred from seeking relief due to the “doctrine of laches.” According to Engel, Gerber “was aware of facts alleged in his complaint and failed to act upon them for a long period of time,” and the defendants took his inaction for granted to their detriment. The seventh defense stated that Gerber’s claims did not comply with the applicable statute of limitations.

According to the eighth defense, Gerber’s claims were not actionable because the purported agreements he alleged they were based on were not in compliance with the applicable Statute of Frauds. (These agreements were presumably the claimed verbal promises made by Stan Lee and Marvel president James Galton.)

Engel closed the brief by stating that the defendants sought dismissal of the complaint, denial of all relief requested by Gerber, reimbursement for legal expenses, and whatever further relief the court deemed appropriate.

(For Donald S. Engel’s February 2, 1981 answer to the lawsuit complaint, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)

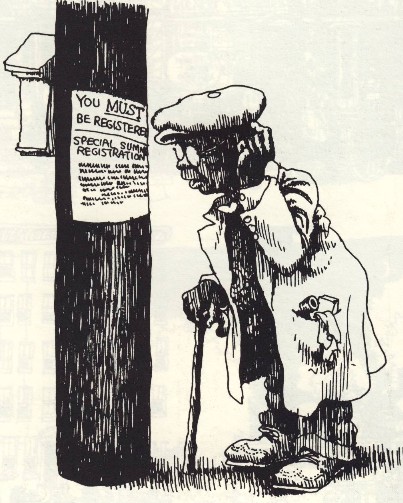

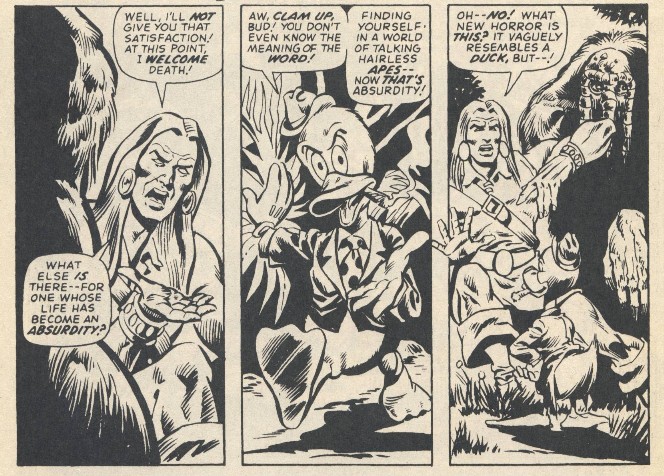

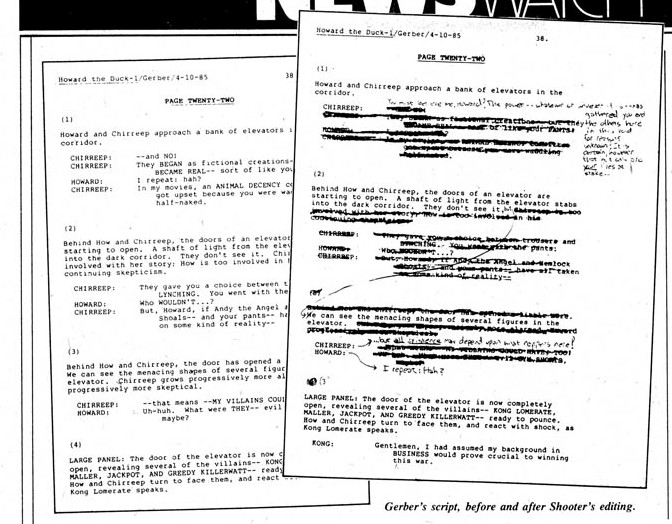

![tcj6211]()

The Comics Journal‘s ironic coverage of the lawsuit. From The Comics Journal #62 (March 1981).

The March 1981 issue of The Comics Journal opened its news section with a story about the case. It included mention of the denied motion to dismiss on jurisdictional grounds. The accompanying graphic ironically featured panels of the first appearance of the “killed off,” “mere proto-type” Howard the Duck instead of the “entirely different,” “much more sophisticated” Howard character Gerber claimed he was actually suing over. The only sources for the story were Gerber and Henry Holmes. There was no indication the Journal made an effort to contact any of the defendants or their attorney Donald S. Engel. There was also apparently no effort to acquire the lawsuit complaint or other filings from Gerber, Holmes, or the court. Judging from the magazine’s subsequent coverage, it never once attempted to get hold of a single document filed in the suit.

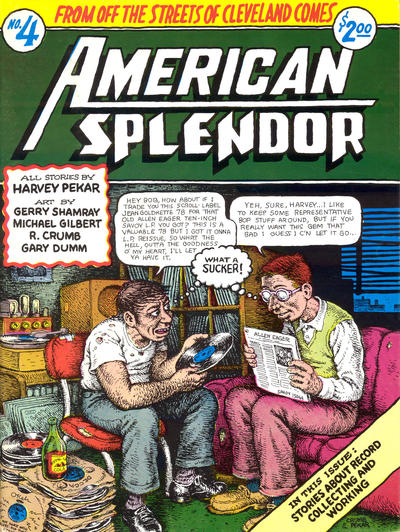

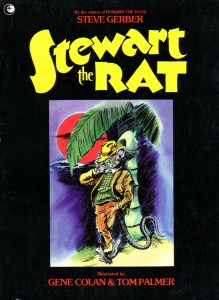

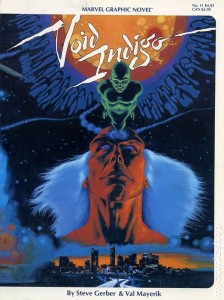

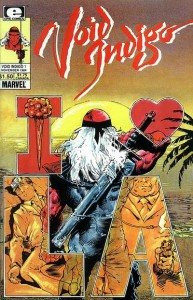

![Destroyer Duck 1]() To help cover his legal bills, Gerber decided to produce a benefit comic book. He wanted to do a feature that satirized his conflict with Marvel and the business environment of the comic-book industry. He asked cartoonist Jack Kirby, whom he knew from Ruby-Spears, to draw the strip. Kirby, generally considered the single most important cartoonist in Marvel’s history, had his own grievances with the company. He consented. The two put together Destroyer Duck, and partnered with Eclipse Enterprises to publish it. The first issue (cover at right) reached comic-book stores in mid-1982. Other contributors included Neal Adams, Alfredo Alcala, Sergio Aragonés, Connie Dobbs, Mark Evanier, Shary Flenniken, Gordon Kent, Steve Leialoha, Martin Pasko, Scott Shaw!, Dan Spiegle, and Joe Staton. Everyone involved donated their efforts. All monies received by Eclipse after printing and shipping costs were deducted went to help pay Gerber’s legal expenses. According to an email from Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney, the issue sold 85,000 copies. Eclipse published six more issues over the next two years.

To help cover his legal bills, Gerber decided to produce a benefit comic book. He wanted to do a feature that satirized his conflict with Marvel and the business environment of the comic-book industry. He asked cartoonist Jack Kirby, whom he knew from Ruby-Spears, to draw the strip. Kirby, generally considered the single most important cartoonist in Marvel’s history, had his own grievances with the company. He consented. The two put together Destroyer Duck, and partnered with Eclipse Enterprises to publish it. The first issue (cover at right) reached comic-book stores in mid-1982. Other contributors included Neal Adams, Alfredo Alcala, Sergio Aragonés, Connie Dobbs, Mark Evanier, Shary Flenniken, Gordon Kent, Steve Leialoha, Martin Pasko, Scott Shaw!, Dan Spiegle, and Joe Staton. Everyone involved donated their efforts. All monies received by Eclipse after printing and shipping costs were deducted went to help pay Gerber’s legal expenses. According to an email from Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney, the issue sold 85,000 copies. Eclipse published six more issues over the next two years.

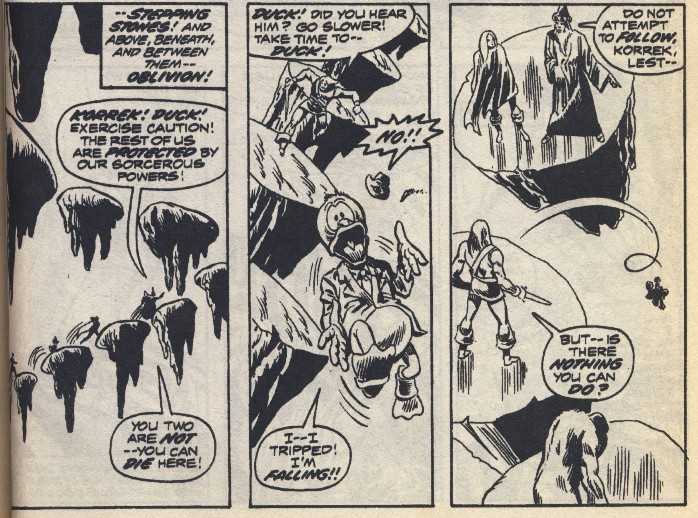

![Kirby]()

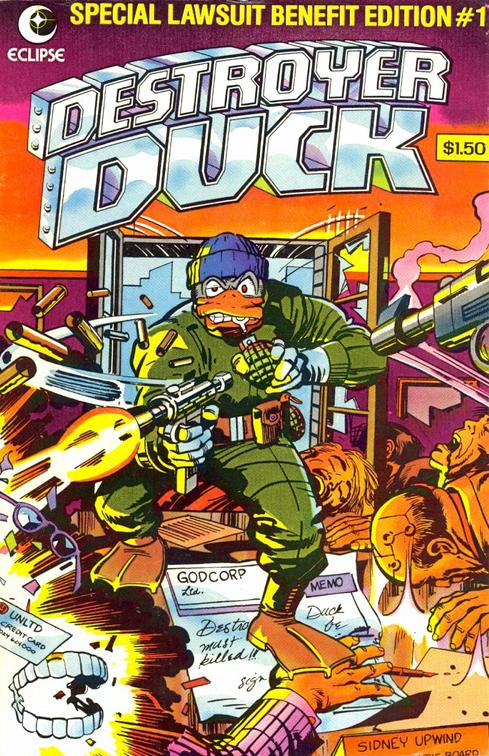

Envelope illustration, by Jack Kirby and Alfredo Alcala, for the 1982 F.O.O.G. (Friends of Old Gerber) benefit art-print portfolio.

Others sought to help Gerber raise money as well. Cerebus cartoonist Dave Sim and his then wife, Deni Loubert, began contacting artists about publishing a benefit art-print portfolio. Gerber told Arthur Byron Cover in 1986 that while he didn’t know of the project beforehand, he gave it his blessing. The F.O.O.G. (Friends of Old Gerber) portfolio, as it came to be titled, featured prints by Sim, Gene Colan (who had left Marvel’s employ in March 1981), Michael Kaluta, Wendy Pini, Marshall Rogers, Frank Thorne, Charles Vess, Barry Windsor-Smith, and Bernie Wrightson. Jack Kirby and Alfredo Alcala provided a picture of the Destroyer Duck character for the envelope illustration.

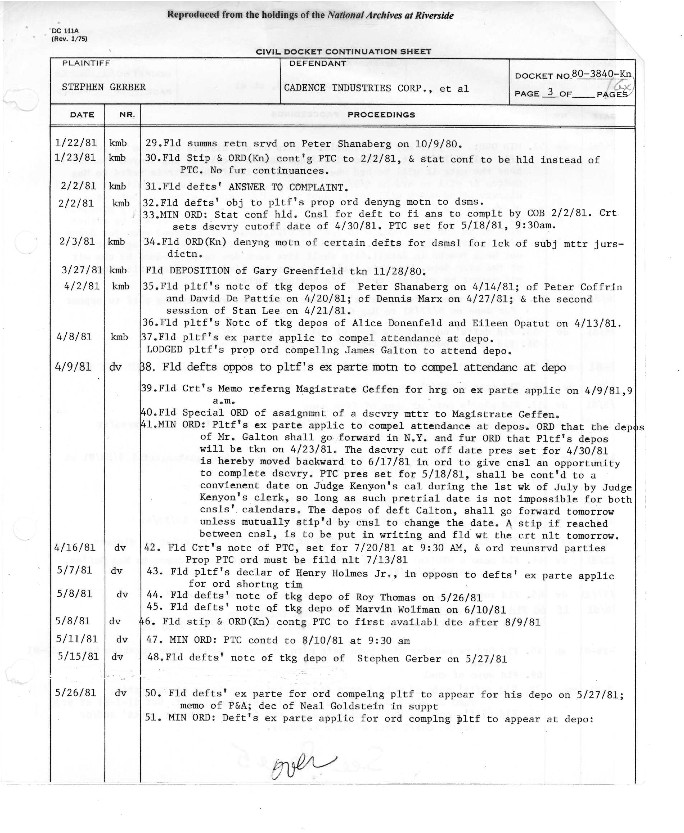

With the filing of the defendants’ answer to Gerber’s complaint, the discovery phase of the lawsuit began. Those deposed: Gerber, Stan Lee, Peter Shanaberg, Morrie Eiseman, Peter Coffrin, Marvel Executive Vice-President for Business Affairs and Licensing Alice Donenfeld, Eileen Opatut (believed to be a Marvel or Cadence staffperson), Marvel Productions executive David DePatie, animation writers Gary Greenfield and Barry Marks (misspelled Marx in the docket), artists Val Mayerik and Frank Brunner, and former Marvel editors-in-chief Roy Thomas and Marv Wolfman. According to Wolfman, he stated in his deposition that he thought Gerber owned the rights to Howard (Dean 42). The court directed Marvel president James Galton to respond to written interrogatories from Gerber’s attorneys, but no notice of his having done so was ever filed. Gerber also filed notice of his intention to depose Marvel sales managers Ed Shukin and Mike Friedrich (misspelled Freederick in the docket), but no notice of those depositions being taken was ever filed, either.

There was a bit of drama related to the depositions. On October 27, 1981, U. S. Magistrate Ralph Geffen ruled that Gerber and his lawyers had been subjected to needless frustrations in their efforts to depose James Galton and Alice Donenfeld. Geffen allowed the two to be deposed through written interrogatories, and ordered Donenfeld to explain any and all attorney-client privilege and work-product objections to answering questions. The defendants were ordered to pay $2,150 in attorneys’ fees to Gerber’s lawyers. On December 15, 1981, Gerber got his own taste of having to pay the other side’s legal bills. After he twice failed to show up for his second deposition, Geffen ordered him to pay the defendants’ attorneys $1,200. Gerber’s request that the deposition be handled through written interrogatories was denied.

(For copies of the October 27 and December 15, 1981 minutes orders, see “The Howard the Duck Documents”.)