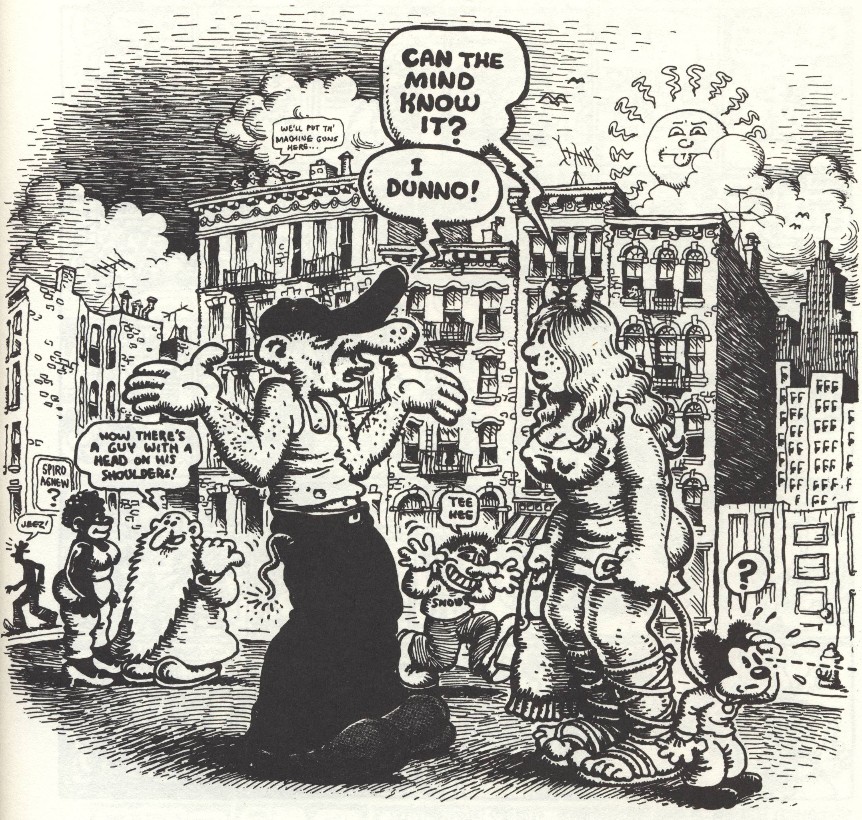

Cover illustration for The East Village Other (1968)

The work of Robert Crumb has its challenges for critics and scholars. He’s been both a restless and prolific artist, and a fairly consistent one in terms of quality. He has rarely committed himself to large projects; his work is mostly short pieces. It’s also unusual for any of those efforts to stand out from one another. Conceptually, he works from impulse, which leads to him maintaining a largely even keel in terms of the strength of his ideas. (It’s all equally strong or equally shallow, depending on one’s general view.) Crumb maintains an even keel in terms of execution as well: the drawing is invariably first-rate, and he never strays outside a certain range with his approach to emphasis and pacing. However, for all that, there’s a fair amount of diversity to his material; one can’t say that if one has read one Crumb strip, one has read them all. Even pieces in the same thematic vein have enough differences to defy efforts to treat one as representative of the whole. A responsibility of critics and scholars, it seems to me, is to distill an artist’s oeuvre down to something more manageable for a prospective audience. Walt Whitman, for instance, published nearly 400 poems in his career compendium Leaves of Grass, but knowledgeable critics can generally limit the number of particularly worthwhile ones down to at most a dozen consensus choices. With Crumb, though, next to no one can agree on which strips to single out, and it’s rare for one to be especially committed to the efforts one picks over others. Designating what constitutes Crumb’s most representative work can create a quandary for anyone who tries.

As such, I certainly understand the inclination to say, as Jeet Heer does, that “the whole of Crumb should be seen as a single project.” If the choices are that difficult to make, then why make them? Isn’t it best to just say there are no short cuts to understanding Crumb’s work? If one wants to engage with his material, one must engage with all of it.

I understand, but I can’t agree. I think it’s an abrogation of critical responsibility. Besides giving new readers a starting point (and highlighting for others what they may have missed), a critic has an obligation to explain what an artist’s work is about and the contribution it makes. This demands highlighting specific efforts (as well as their most accomplished aspects) to make those arguments. Claiming that it’s all one project–and, implicitly, of equal significance—allows the critic to sidestep this duty. If one doesn’t make choices and argue for them, I’m not sure one can be said to be engaging with Crumb’s work very deeply at all. Breaking down his career into more manageable pieces is necessary.

When editing the results of the Best Comics Poll last year, I hit upon the idea of categorizing Crumb’s work by period. This is the strategy art historians use when dealing with figures such as Picasso, and I think it’s also applicable to Crumb. When it comes to getting a handle on Crumb’s career, this probably offers the best way to go about it. One can characterize the material in terms of the various periods—I believe the groupings are easier to agree on than the relative merit of individual pieces—and then highlight the efforts one feels best reflects Crumb’s work at the time in question. With the poll, I designated two of Crumb’s periods as the Counterculture Era and the Weirdo Era. I’d like to expand on that with a list of six distinct periods covering his entire career: Tyro, Early Counterculture, Later Counterculture, Post-Counterculture, Weirdo, and Illustration. The categories aren’t perfect; there’s certainly overlap between them, and I’m sure someone can probably find better names for them. But I think they sum up Crumb pretty well. The following are my thoughts on the periods and what one will find in them. I would have liked to have been specific about additional individual efforts, but this essay is intended as more of a starting point than a definitive discussion.

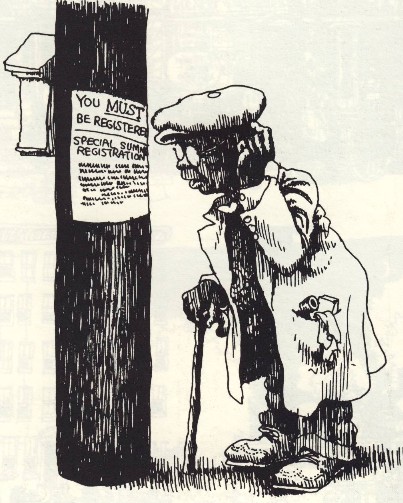

From Crumb’s Harlem series (1965)

The Tyro period begins with Crumb’s amateur strips and fanzines from his adolescence. It includes his career as an aspiring commercial artist, and ends in 1966. For the most part, what one sees here is Crumb developing his craft as a draftsman and cartoonist. The highlights include Crumb’s greeting-card work, the Harlem and Bulgaria illustrations he produced for Help! magazine, and the 1960s adventures of Fritz the Cat. (The Fritz stories weren’t published until 1968 and 1969, but Crumb drew them in 1964 and 1965.) If one has a set of Fantagraphics Books’ The Complete Crumb Comics handy, this is the material in the first three volumes. The highlights all appear in the third book.

The work of the Early Counterculture period is the material that earned Crumb his fame, and I firmly believe it is far and away his most important contribution. These are the comics from 1967 and 1968, and they include the strips in Zap Comix #0 and 1, the Cheap Thrills album cover for Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the various contributions to underground newspapers such as Yarrowstalks and The East Village Other. (These strips are featured in The Complete Crumb Comics Volumes 4 and 5, as well as in the Head Comix collection.) With this work, Crumb introduced the thinking of the Beats (and their Surrealist forebears) to comics. The work rejected the sanitized, conformist, and commercialized modes that defined the field. Instead, it embraced an improvisatory spirit, complete freedom of imagination, and a sardonic, gritty view of the surrounding world.

From Zap Comix #1 (1967)

Conceptually, the work also reflected–even anticipated–a major development in the world of fine art. The dominant mode of painting in the 1950s had been abstract expressionism, which had taken existentialist improvisation to its extreme end: content was gone; all that mattered was evoking impulse, feeling, and mood in stroke, line, and color. Pop Art, the movement that followed, was the opposite: it favored dissonance over direct emotion, and it embraced the totems of the commercial culture that abstract expressionists were rejecting through their move away from representationalist thinking. The late 1960s brought a synthesis: the imagery and styles of popular culture were imbued with the abstract expressionists’ existential intensity. The key figure in painting was Philip Guston, a former abstract expressionist who used cartoon Klansmen and Cyclopses to dramatize feelings of doubt, anxiety, and self-loathing. Crumb, whose Early Counterculture work preceded the Guston paintings by a couple of years (Guston’s first cartoon paintings were done in 1969) was working in the same stylistic space: the imagery of commercial art–particularly that of the Depression era–was made to serve his every expressive impulse and narrative whim. The Early Counterculture work not only defined Crumb as a major figure in the world of comics; it’s earned him a spot in the history of 20th century visual art as well.

The Later Counterculture period, which encompasses 1969 through 1976 (Volumes 5 through 11 of The Complete Crumb Comics), may very well feature Crumb’s most controversial work. Jeet Heer, for one, has identified this as the period when Crumb became Crumb. As Heer notes, Crumb came under the influence of S. Clay Wilson: “Wilson was the artist who unchained Crumb’s unconscious, who gave the final push for Crumb to shove aside his internal censor and be utterly honest…” Heer and others feel this work is when Crumb came into his own as an artist, but others, including myself, see it as when his work turned a nasty corner. Conceptually, it degenerated into a very ugly solipsism. It’s marked by a fascination with taboo: racism, violent misogyny, incest, sexualized children—all rendered from the mindset of a pornographer. A harsh—though intellectually shallow—anger towards society emerges as well. Crumb did some of his most popular work during this period—Home Grown, by some accounts, is his best-selling publication—but others may find the material boorish and fundamentally uninteresting.

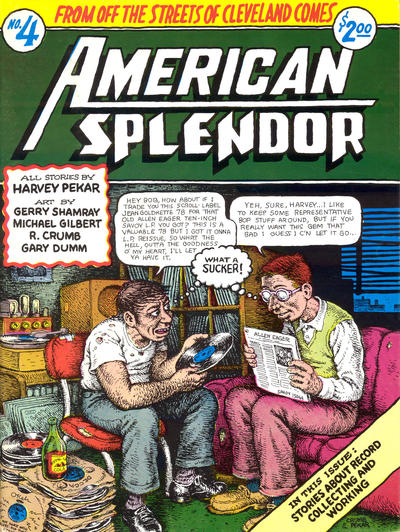

Cover to American Splendor #4 (1979)

I have to say that the most impressive material from the Post-Counterculture period—published between 1976 and 1979 and featured in The Complete Crumb Comics, Volumes 12 and 13—are among my favorites of Crumb’s work. It was during this period that Harvey Pekar began publishing his memoir-comics series American Splendor. Crumb was one of the cartoonists Pekar enlisted to illustrate the stories, and serving another creator’s material got Crumb’s thinking out of the misanthropic box in which it had become so distastefully trapped. Pekar’s scripts, though gritty, didn’t reflect the same kinds of attitudes. The material was humane, it valued naturalism, and it relied on quiet ironies for its effects. The demands of illustrating it seemed to awaken something in Crumb. He developed an impressive command of dramatic nuance while working on the stories. I’m not alone in thinking these collaborations are among the best comic-book comics of the pre-graphic-novel era.

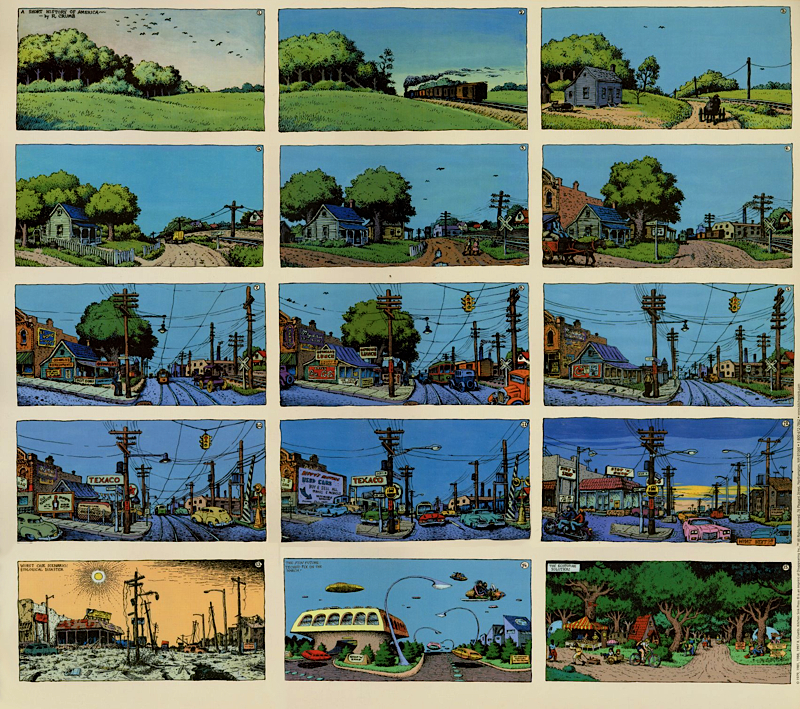

“A Short History of America” (1979; expanded 1988)

The American Splendor comics aren’t even the best work Crumb did during this time. That honor goes to 1979’s “A Short History of America,” a 12-panel strip (expanded to 15 panels in 1988) that was first published in the CoEvolution Quarterly. At the time, Crumb had been doing some environmentally themed editorial cartoons for the publication, but this piece certainly ranks all of them. It focuses on a single expanse of land from decades past, and, in each succeeding panel, shows how that land evolved with the times up to the present day. It’s poetic; Crumb defines and redefines the image so that the changes to it become the piece’s content. And for once, Crumb is understated with his social critique, and the dispassionate tone makes the point—namely the corruptions of the land brought about by technological development—all the more powerful. It’s a devastatingly effective piece of work.

However, as strong as the best of the material from the Post-Counterculture period is, a good deal of it is among the worst of Crumb’s career. Apart from the work with Pekar and the CoEvolutionioary Quarterly, Crumb was more acidly misanthropic than ever. As R. Fiore wrote in 1988, “As the ‘70s wore on Crumb wore down. Crumb’s stories got to be like a continuing saga entitled Four Pages of Bitching.” Fiore also notes that things got to the point where he gave on entirely on Crumb’s work for a time. He’s not kidding about the distastefulness; the material is extremely repetitive and tiresome.

Many think that the work from the Weirdo period, from 1980 to 1993 (and largely collected in Volumes 14 through 17 of The Complete Crumb Comics) constitutes Crumb’s best work. If one is of the opinion that the Late Counterculture work is better than that from the Early Counterculture period, I can understand how one comes by that judgment. However, it’s not one I share. Crumb is still stuck in the same box. The major difference is that the dramatic skills he developed while working with Pekar allow the material to breathe a bit more. Also, his CoEvolutionary Quarterly work sparked a greater interest in rendering technique, and the art gains a superficial gravitas. But conceptually, it’s not much different than the bulk of the material he produced during the 1970s. The efforts at satire are shrill and shallow, and often devolve into rants. He tries his hand at Pekar-style verité pieces, but these tend to be tiresomely self-pitying on the one hand, or outright obnoxious on the other. (The nadir of the latter is probably “Memories Are Made of This,” in which he recounts his date-rape of an acquaintance.) Again, the highlights come when Crumb has to engage with another creator and get out of his own head. His collaborations with wife Aline Kominsky-Crumb have a pleasant breeziness, and he does well with a few of the adaptation pieces (such as of Boswell or Kraft-Ebbing). Crumb fans will certainly find the period of interest. One can easily see his development from what came before, as well as the seeds for what comes next.

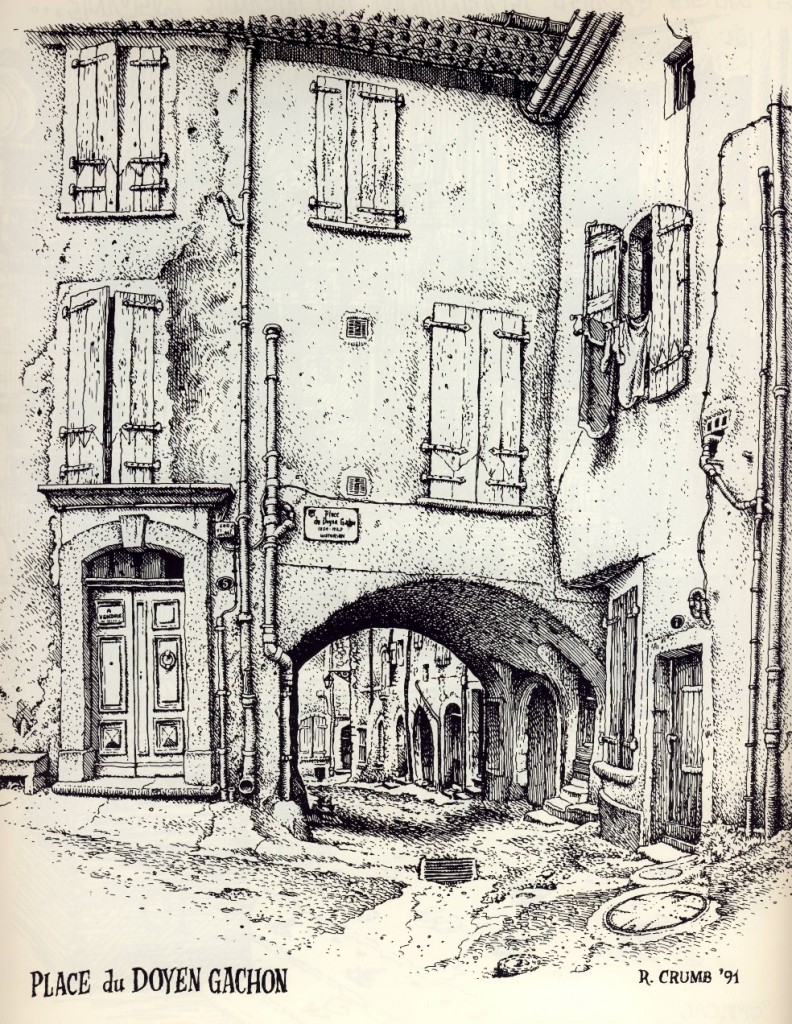

From the Vues de Sauve portfolio (1991)

After the Weirdo period, Crumb entered what I call the Illustration period, which is where he is now. He doesn’t appear terribly interested in producing comics anymore; his efforts for the past two decades have been largely given over to producing single-image illustrations. It’s a logical progression from his work in the 1980s. As noted, he developed a greater interest in rendering technique, and his most striking efforts during that time are probably the intensively cross-hatched cover drawings he produced for Weirdo magazine. When one looks at his best work from the Illustration period, namely the two Art & Beauty issues, or the Vues de Sauve portfolio pieces, one sees an artist who just wants to enjoy his ability to make handsome pictures. Introducing Kafka and The Book of Genesis, the two major comics projects, seem in retrospect efforts to find a halfway point between comics and illustration, but the stale dramatizations in the latter demonstrate that comics no longer much engage Crumb’s interest. If one approaches Genesis as a collection of single-image illustrations of the Biblical verses, it seems a more successful effort. I’m starting to view the project as a coda to his career; it’s certainly more that than the magnum opus it was hyped as. Illustration may be the place Crumb has chosen to retire.

In closing, this is one comics critic’s analysis and judgments of Crumb’s career. I hope it’s of more interest than a pronouncement that his work is a single big project and one should just read all of it. Breaking his work down into distinct periods does, I think, help one to get a better handle on Crumb, no matter what one’s opinion of this or that individual effort. I certainly don’t think this essay is the last word. With Crumb, no essay ever is.